Peptic Ulcer Symptom Checker

This tool helps you assess whether your severe stomach pain might be related to a peptic ulcer. It is NOT a substitute for professional medical diagnosis. If you have severe symptoms, please seek immediate medical attention.

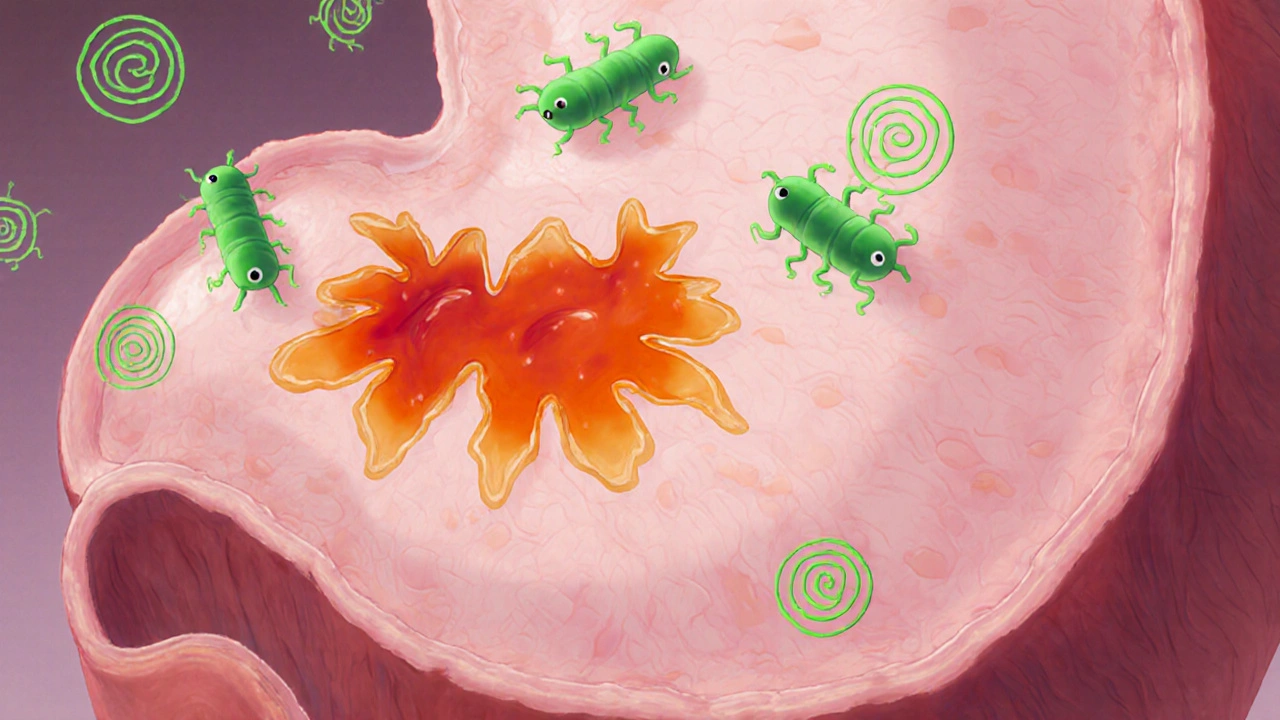

Ever wondered why a sharp, relentless ache in your belly can feel like something is literally tearing you apart? That kind of severe stomach pain refers to intense discomfort in the upper abdomen that often signals a deeper issue. One of the most common culprits behind this agony is a peptic ulcer a sore that forms on the lining of the stomach, small intestine, or esophagus due to acid erosion. Understanding how these two connect can help you spot the warning signs early, get the right tests, and start treatment before things get worse.

What Exactly Is a Peptic Ulcer?

A peptic ulcer is an open sore that develops on the inner lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer), the first part of the small intestine (duodenal ulcer), or the lower esophagus (esophageal ulcer). The ulcer forms when the protective mucous layer breaks down and gastric acid and digestive enzymes start eating away at the tissue. Most ulcers are categorized under two heads: gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers, but both can produce that dreaded, crushing pain.

Why Severe Stomach Pain Often Signals an Ulcer

The pain from an ulcer isn’t just a mild nuisance - it’s usually described as a burning, gnawing, or cramping sensation that peaks when the stomach is empty and eases after you eat or take antacids. That pattern is a clue that acid is directly irritating the ulcerated area. When the ulcer penetrates deeper, the pain can become sharp, radiate to the back, and even cause nausea or vomiting. In severe cases, the ulcer can bleed, leading to dizziness, black‑tarry stools, or a sudden drop in blood pressure.

Main Triggers Behind Peptic Ulcers

Several well‑studied factors can tip the balance in favor of ulcer formation. Below are the biggest players you’ll hear about:

- Helicobacter pylori a spiral‑shaped bacterium that lives in the stomach lining and weakens its defenses against acid. About 70% of duodenal ulcers and 30% of gastric ulcers are linked to this infection.

- NSAIDs non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin that inhibit prostaglandin production, reducing the stomach’s protective mucus. Regular use, especially without food, dramatically raises ulcer risk.

- Gastric acid hydrochloric acid secreted by parietal cells to aid digestion; excess or uncontrolled secretion can erode the lining. Overproduction can be triggered by stress, smoking, or certain diets.

- Stress ulcer ulcers that develop in response to severe physiological stress such as trauma, surgery, or critical illness. The body’s stress response increases acid output and reduces blood flow to the stomach lining.

- Lifestyle habits - excessive coffee, alcohol, and smoking each weaken the mucosal barrier and stimulate acid release.

Symptoms to Watch - When to Call a Doctor

If you’re dealing with any of the following, it’s time to seek professional help:

- Persistent burning pain in the upper abdomen, especially on an empty stomach.

- Pain that improves after meals or antacid use but returns a few hours later.

- Nausea, vomiting, or a feeling of fullness after eating small amounts.

- Dark, tar‑colored stools or vomiting blood (signs of bleeding ulcer).

- Unexplained weight loss or loss of appetite.

These symptoms overlap with other conditions-like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD a chronic condition where stomach acid flows back into the esophagus causing heartburn)-so proper diagnosis is key.

How Doctors Diagnose an Ulcer

The diagnostic pathway usually starts with a detailed medical history and physical exam. From there, several tests can confirm the presence and cause of an ulcer:

- Endoscopy a minimally invasive procedure where a flexible tube with a camera examines the stomach lining and can take biopsies. This is the gold standard for visualizing ulcer size, depth, and checking for bleeding.

- Non‑invasive H. pylori testing via breath, stool, or blood sample.

- Imaging studies like barium swallow or CT scan if complications such as perforation are suspected.

Once the ulcer is identified, the treatment plan is shaped around its cause.

Treatment Options - What Works Best?

Healing a peptic ulcer revolves around three goals: eliminate the cause, suppress acid, and protect the lining. Below is a quick look at the most common therapies, followed by a side‑by‑side comparison.

| Medication Class | How It Works | Typical Use | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) | Blocks the final step of acid production in parietal cells | First‑line for most ulcers; 4-8 weeks | Headache, mild diarrhoea, rare nutrient malabsorption |

| H2 Blocker | Reduces acid by blocking histamine receptors | Mild to moderate ulcers or maintenance after PPI | Drowsiness, constipation, dizziness |

| Antibiotic Regimen | Eradicates H. pylori bacteria | Combined therapy (e.g., clarithromycin + amoxicillin + PPI) for 10‑14 days | Metallic taste, nausea, risk of antibiotic resistance |

| Antacids | Neutralises stomach acid instantly | Short‑term symptom relief; not a healing agent | Rebound acid production, constipation or diarrhoea |

For most patients, a Proton pump inhibitor such as omeprazole, esomeprazole, or lansoprazole, is the cornerstone of therapy. If H. pylori is present, the doctor adds a carefully timed antibiotic course. Lifestyle tweaks-quitting smoking, limiting alcohol, and avoiding NSAIDs when possible-greatly boost healing speed.

Practical Prevention Tips

Even after the ulcer heals, staying ulcer‑free takes some daily habits:

- Take NSAIDs with food or switch to acetaminophen for pain if possible.

- Limit coffee, spicy foods, and carbonated drinks that can irritate the lining.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in fiber, fruits, and vegetables-these help buffer stomach acid.

- Manage stress through exercise, meditation, or adequate sleep; chronic stress fuels acid spikes.

- If you test positive for H. pylori, complete the full antibiotic regimen even if symptoms improve early.

Regular check‑ups are wise, especially for those with a history of ulcers or chronic NSAID use.

When Things Get Complicated

Rarely, an ulcer can perforate, bleed heavily, or cause a blockage. Those emergencies need hospital care-often surgery to close the hole or stop the bleed. Warning signs include sudden, severe abdominal pain that worsens with movement, vomiting blood, or fainting.

Quick Checklist for Managing Severe Stomach Pain Linked to Ulcers

- Identify the pattern: pain on an empty stomach, relief after eating or antacids?

- Check for red‑flag symptoms: vomiting blood, black stools, dizziness.

- See a doctor for endoscopy or H. pylori testing.

- Start prescribed PPI (or H2 blocker) and complete any antibiotic course.

- Eliminate or reduce NSAID use; switch to safer pain relievers.

- Adopt ulcer‑friendly habits: no smoking, limit alcohol, manage stress.

- Follow‑up after 4‑8 weeks to confirm healing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can severe stomach pain be caused by something other than an ulcer?

Yes. Conditions such as gallstones, pancreatitis, GERD, irritable bowel syndrome, and even certain infections can produce similar pain. A proper medical evaluation is essential to rule out these possibilities.

How long does it take for an ulcer to heal?

With appropriate therapy-usually a PPI plus, if needed, antibiotics-most ulcers heal within 4 to 8 weeks. Follow‑up endoscopy may be recommended for larger or recurrent sores.

Are over‑the‑counter antacids enough to treat an ulcer?

Antacids only neutralise acid temporarily and don’t promote healing. They can relieve discomfort while you’re waiting for prescription medication to take effect, but they’re not a cure.

What lifestyle changes help prevent ulcer recurrence?

Quit smoking, limit alcohol, avoid regular NSAID use, eat a balanced diet low in highly acidic or spicy foods, and manage stress through regular exercise or relaxation techniques.

Is it safe to take a PPI for more than eight weeks?

Short‑term use (up to 8 weeks) is generally safe. Longer courses should be monitored by a doctor because of potential risks like nutrient malabsorption, increased infection rates, and bone density loss.

Antonio Estrada

October 16, 2025 AT 14:57Understanding severe stomach pain in the context of peptic ulcers requires both anatomical insight and lifestyle awareness. The ulcer itself is a breach in the mucosal barrier, exposing delicate tissue to corrosive gastric acid. When acid repeatedly contacts this exposed area, the nervous endings send sharp, burning signals that manifest as intense abdominal discomfort. Because the stomach is often empty during the night or between meals, patients notice the pain most acutely on an empty stomach. Eating temporarily buffers the acid, which is why many describe relief after a small meal or antacid. However, this relief is only short‑term; the underlying lesion remains and can worsen. Chronic use of NSAIDs further impairs the protective mucus, accelerating ulcer formation. Helicobacter pylori infection acts like a stealthy saboteur, eroding the defensive layer from within. Stress, while not a direct cause, can increase acid output and reduce blood flow to the gastric lining, compounding damage. The body’s natural healing processes are constantly battling these assaults, but they need a favorable environment to succeed. Eliminating smoking and excessive alcohol removes two major irritants that stimulate acid secretion. Balanced nutrition rich in fiber and antioxidants supports mucosal repair. Adequate sleep and stress‑management techniques lower catecholamine spikes that provoke acid surges. Pharmacologically, proton‑pump inhibitors provide a powerful shield by shutting down the final step of acid production. When H. pylori is present, a targeted antibiotic regimen is essential to eradicate the pathogen and prevent recurrence. Finally, regular follow‑up ensures that the ulcer has healed and that no complications, such as bleeding or perforation, have arisen.

Andy Jones

October 17, 2025 AT 04:50Wow, another article that pretends to be original while basically re‑hashing what every gastro‑textbook has been shouting for decades-yes, ulcers are caused by acid, NSAIDs, and that notorious H. pylori, not some mystical “stomach demon.”

Kevin Huckaby

October 17, 2025 AT 15:57😂 Sure, but let’s not forget that the “stomach demon” might just be the stress of watching our favorite sports team lose! 🍕🔥💥

Brandon McInnis

October 18, 2025 AT 08:37Reading through this feels like embarking on an epic quest where the hero battles fiery dragons-only here the dragons are relentless acid waves, and the armor is our disciplined habits, courage, and a trusty prescription.

Chris Smith

October 18, 2025 AT 16:57yeah the drama is real but the meds do the job

Maribeth Cory

October 19, 2025 AT 06:50Great rundown! Remember, taking small steps like swapping ibuprofen for acetaminophen and adding a daily walk can make a massive difference in healing.

andrea mascarenas

October 19, 2025 AT 12:24Absolutely keep the momentum and follow the doctor’s plan

Vince D

October 19, 2025 AT 23:30Stop ignoring the warning signs.

Camille Ramsey

October 20, 2025 AT 07:50Honestly, if you keep poppin' those NSAIDs like candy, you're just invitin' a ulcer to the party-get your act together and read the instructions, ya know?

Scott Swanson

October 20, 2025 AT 18:57Sure, because nothing says “I care about my health” like treating your stomach like a demolition site-maybe try a little self‑respect next time?

Karen Gizelle

October 21, 2025 AT 08:50Look, I get that strugglin with pain is rough, but you cant just ignore the red‑flags. If you see black tar stool or vomit blood, that's a siren. Don't be lazy-go see a doctor ASAP. Trust me, it's better than wingin it at home.

Stephanie Watkins

October 21, 2025 AT 17:10Do you think there are any early signs that differentiate an ulcer from, say, gallbladder issues before they become severe?

Zachary Endres

October 22, 2025 AT 04:17Imagine your gut as a battlefield; every healthy choice is a soldier marching toward victory, and every ulcer is a defeated enemy retreating. Keep the troops strong, and the war will be won!

Ashley Stauber

October 22, 2025 AT 12:37While optimism helps, some patients just don’t respond to standard therapies, so it’s important to consider alternative diagnostics.

Amy Elder

October 23, 2025 AT 02:30Stay positive keep focusing on healthy habits

Erin Devlin

October 23, 2025 AT 10:50Healing is a dialogue between body and choice.