When you pick up a prescription at your local pharmacy, you might not think twice if the pill in the bottle looks different from last time. That’s generic substitution - a routine part of retail pharmacy. But if you’ve ever been hospitalized, you’ve likely experienced something entirely different: therapeutic interchange. These aren’t just different names for the same thing. They’re two distinct systems, shaped by different rules, goals, and risks. Understanding how they work - and how they fail to talk to each other - can help you avoid dangerous gaps in your care.

How Retail Pharmacies Handle Substitution

In retail settings, substitution is mostly about cost. When a doctor writes a prescription for a brand-name drug like Lipitor, the pharmacist doesn’t just hand it over. They check the insurance plan’s formulary. If a generic version of atorvastatin is approved and cheaper, they swap it in - unless the doctor or patient says no. This is legal in all 50 states. In fact, 90.2% of eligible outpatient prescriptions are filled with generics, saving patients and insurers billions every year.

The pharmacist makes this call at the counter. No committee. No consult. Just a quick look at the formulary and a quick question: "Do you want the generic?" Thirty-two states require a verbal warning. Eighteen require written consent the first time you’re switched. That’s the law. But in practice, many patients don’t even notice. A 2023 Consumer Reports survey found 14.3% of people thought their medication changed because the doctor switched it - not the pharmacy.

Most substitutions happen with oral tablets and capsules. Only 12.7% of specialty drugs - like those for cancer or autoimmune diseases - are even eligible for substitution. Insurance rules often block them. But even when allowed, the risk of confusion is higher. One pharmacist in Sydney told me about a patient who refused a generic for gabapentin because the pill was blue instead of yellow. She’d been on the brand for years. The color change scared her. She didn’t know it was the same drug.

How Hospital Pharmacies Handle Substitution

Hospitals don’t operate like corner drugstores. There’s no walk-in customer. No insurance formulary at the register. Instead, substitution happens behind the scenes - through Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees. These are groups of doctors, pharmacists, and administrators who decide which drugs are allowed on the hospital’s formulary. If a cheaper, equally effective drug becomes available, they vote to replace it. Not just for one patient - for everyone.

This isn’t about saving money on a single prescription. It’s about changing how entire units treat patients. For example, a hospital might switch from vancomycin to linezolid for MRSA infections because it’s easier to give orally, reduces IV complications, and cuts costs. But that change doesn’t happen overnight. It requires training 15 different medical teams. It needs updated protocols. It requires alerts in the electronic health record.

And it’s not just pills. Nearly 70% of hospital substitutions involve IV medications, biologics, or complex compounded drugs - things you’d never see at a retail pharmacy. These aren’t simple swaps. They’re clinical decisions. A 2022 ASHP survey found 84.6% of hospital pharmacists base substitution on patient-specific factors - kidney function, allergies, drug interactions - not just price.

Why the Two Systems Don’t Talk

Here’s where things get dangerous. A patient gets discharged from the hospital with a new medication - maybe a drug they were switched to during their stay. They go home. Their primary care doctor hasn’t been told about the change. The retail pharmacist, seeing a brand-name prescription, assumes the doctor meant the brand. They dispense it. The patient takes it. But the hospital had switched them to a generic. Now they’re getting two different versions. Or worse - the hospital switched them to a different drug entirely, and the retail pharmacy doesn’t know.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices found that 23.8% of medication errors during hospital-to-home transitions are tied to substitution mismatches. That’s not a small number. That’s a system failure. One patient in Sydney was switched from warfarin to apixaban in the hospital. The discharge summary mentioned it. But the retail pharmacy didn’t have access to that note. They filled the original warfarin script. The patient ended up back in the ER with a clot.

Documentation doesn’t match. Systems don’t talk. Insurance rules override clinical decisions. Retail pharmacies follow state laws. Hospitals follow Joint Commission standards. Neither system was designed to hand off care to the other.

Who Decides? Who Gets Informed?

In retail, the pharmacist decides - and must inform the patient. That’s the law. But in hospitals, the pharmacist doesn’t decide alone. The P&T committee does. And the patient? They rarely get told. The doctor might mention it. But often, the change is buried in a discharge summary no one reads.

And the notifications? They’re backwards. Retail pharmacies must notify patients - but only about generics. Hospitals must notify physicians - but only after the change is made. No one notifies the patient about a therapeutic interchange unless they ask. That’s a gap. And it’s growing.

What’s Changing - and What’s Not

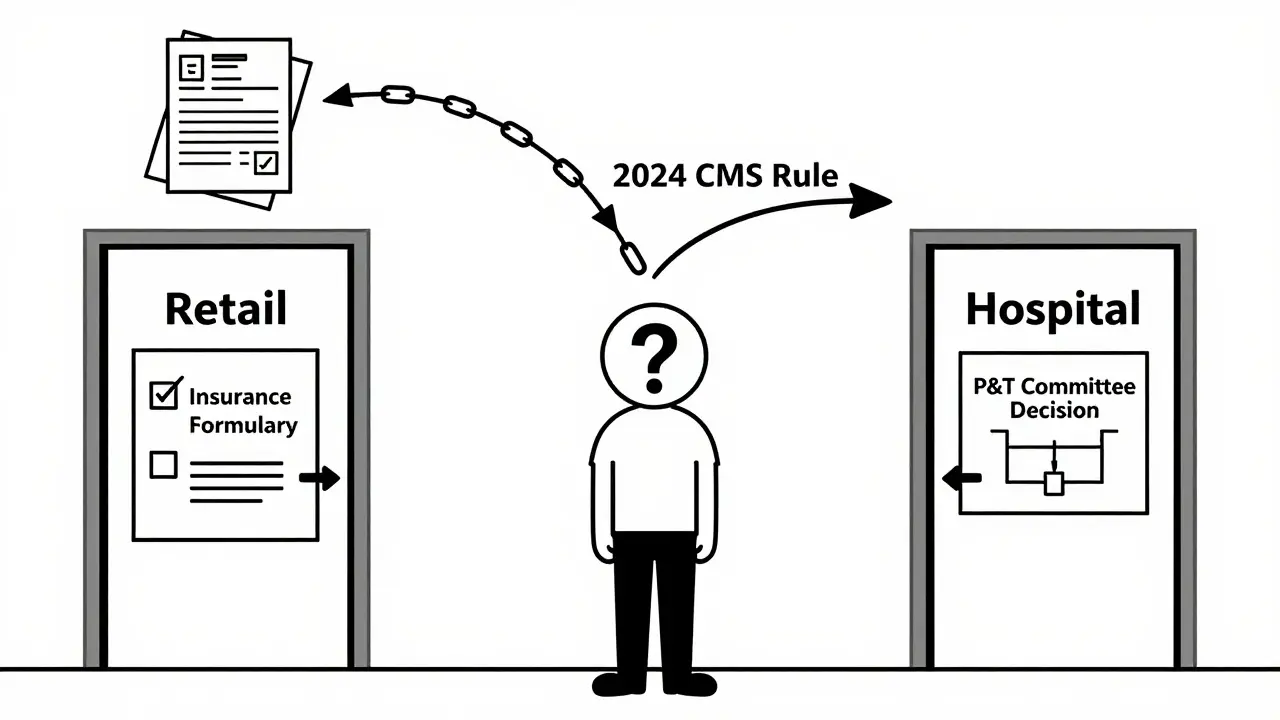

There’s movement toward alignment. The 2023 CMS Interoperability Rule, effective in July 2024, will force hospitals and pharmacies to share substitution records electronically. Epic and Cerner are building modules that will flag a patient’s hospital substitution history when they walk into a retail pharmacy. That’s a big step.

But it won’t fix everything. Retail pharmacies still rely on insurance formularies. Hospitals still rely on P&T committees. The goals are different: one saves money, the other optimizes care. And until those goals align, substitution will remain two separate worlds.

What’s clear? Patients are caught in the middle. A 2023 APhA pilot program showed that when retail and hospital teams coordinated substitution, readmission rates dropped by 22%. That’s not magic. That’s communication.

What You Can Do

If you’re switching between hospital and retail care, don’t assume anything. Ask:

- "Was my medication changed while I was in the hospital?"

- "Is this the same drug, or a different one?"

- "Can you check if my hospital discharge summary matches what you’re giving me?"

Keep a list of all your medications - including doses and why you’re taking them. Bring it to every appointment. If your retail pharmacist doesn’t ask about your hospital stay, tell them. You’re not being difficult. You’re preventing a mistake.

Can a retail pharmacist substitute any generic drug?

No. Retail pharmacists can only substitute drugs that are deemed therapeutically equivalent by the FDA and allowed by state law. They also can’t substitute if the prescriber writes "Dispense as Written" or "Do Not Substitute." Insurance formularies also limit which generics are covered. Some drugs - like insulin, biologics, and certain epilepsy medications - have strict substitution rules or are not eligible at all.

Why can’t hospitals just use retail substitution rules?

Because hospital care is more complex. A retail pharmacy fills one prescription at a time. A hospital treats hundreds of patients daily with varying conditions, allergies, and organ function. Therapeutic interchange isn’t about cost - it’s about clinical safety. A drug that works for one patient might be dangerous for another. Hospital pharmacists use data, guidelines, and team input to make those calls - not just a formulary.

Do hospital pharmacists ever make substitutions at the bedside?

Rarely. Most substitutions are planned by the P&T committee and built into the hospital’s formulary. But in emergencies - like a drug shortage or a life-threatening allergy - pharmacists can make immediate, temporary substitutions. These are documented and reviewed afterward. It’s not routine, but it’s part of their safety net.

Why do hospital substitutions involve IV drugs more than retail ones?

Because IV medications are expensive, risky, and often used in critical care. A hospital might switch from a costly IV antibiotic to a cheaper, equally effective one to reduce costs and improve safety. For example, switching from piperacillin-tazobactam to cefepime can cut costs and reduce side effects. Retail pharmacies rarely handle IV drugs - they’re given in hospitals, not dispensed for home use.

Is generic substitution always safe?

For most people, yes. The FDA requires generics to be bioequivalent to brand-name drugs. But for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine - even small changes in absorption can matter. That’s why some doctors prefer to keep patients on the same brand. It’s not because generics are unsafe - it’s because consistency matters more than cost in these cases.

If you’re managing medications across hospital and retail settings, the key isn’t knowing the rules - it’s asking questions. Your health is not a transaction. It’s a thread - and substitution is a knot that can come loose if no one’s holding the ends.

Maddi Barnes

February 18, 2026 AT 06:45Wow. Just... wow. 😅 So let me get this straight - retail pharmacists are basically the gatekeepers of your wallet, while hospital pharmacists are the quiet geniuses trying to keep you from dying? And we wonder why people end up back in the ER? I once got switched from brand to generic levothyroxine and spent three weeks feeling like a zombie. My doctor didn’t even know. The pharmacy? They said ‘it’s the same thing.’ No, Karen. It’s not. 😭

Benjamin Fox

February 18, 2026 AT 12:32Jonathan Rutter

February 18, 2026 AT 19:31You think this is bad? Wait till you find out how many people are getting switched to generics that have different fillers - corn starch, lactose, dyes - and they don’t even know they’re allergic. I had a friend who went into anaphylaxis because the generic had a dye her body hated. The pharmacist? Said ‘it’s FDA approved.’ Oh honey. FDA doesn’t care if you die. They care if the pill dissolves in 10 minutes. And don’t even get me started on how hospitals just change your meds without telling you. It’s systemic neglect. We’re treating humans like inventory.

Jana Eiffel

February 20, 2026 AT 17:51It is a profound epistemological failure of our healthcare infrastructure that therapeutic decision-making is bifurcated along commercial and clinical axes. The epistemic authority vested in the P&T committee is not only scientifically rigorous, but ethically superior to the commodified substitution protocols of retail pharmacies. The ontological disjunction between institutional and outpatient pharmacology reveals a deeper crisis of care as transaction.

John Cena

February 21, 2026 AT 12:49aine power

February 22, 2026 AT 15:40Tommy Chapman

February 22, 2026 AT 22:02Irish Council

February 24, 2026 AT 07:14Freddy King

February 24, 2026 AT 09:14Let’s deconstruct the operational asymmetry here. Retail: formulary-driven, payer-centric, volume-optimized. Hospital: protocol-driven, outcome-centric, risk-mitigated. The disconnect isn’t accidental - it’s structural. The EHR interoperability mandate is a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. What we need is unified clinical governance. Not tech. Not policy. Culture. And nobody’s ready for that.

Laura B

February 25, 2026 AT 06:25I work in a hospital pharmacy and I can tell you - we spend HOURS debating substitutions. We look at kidney function, age, other meds, history, allergies, even the patient’s mood. Retail? They check the formulary and hand you a pill. I’ve had patients cry because they got a different color pill and thought they were being poisoned. We need to bridge this gap. It’s not just paperwork - it’s trust.

Robin bremer

February 27, 2026 AT 04:35Jayanta Boruah

February 27, 2026 AT 17:32While the systemic analysis presented is commendable, one must recognize the fundamental epistemological hierarchy that underpins hospital formularies. The P&T committee operates under evidence-based guidelines derived from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. Retail substitution, by contrast, is governed by actuarial models and insurer incentives. The disparity is not merely procedural - it is ontological. To equate the two is to misunderstand the very nature of clinical governance. Moreover, the assertion that patients are ‘caught in the middle’ is inaccurate. Patients are not passive victims - they are stakeholders who must be educated. The onus lies not solely with institutions, but with the individual to inquire, to verify, to demand transparency. This is not negligence - it is negligence enabled by apathy.

Hariom Sharma

March 1, 2026 AT 10:05Man, I’ve been through both systems - hospital and retail. You know what saved me? Asking. Just asking. ‘Hey, did my meds change in the hospital?’ ‘Can you check the discharge note?’ It’s not hard. And honestly? Pharmacists appreciate it. They’re overworked. But they want to help. I started carrying my med list on my phone. Now my whole family does. Small thing. Big difference. Keep asking. Keep caring. You’re your own best advocate.

Nina Catherine

March 1, 2026 AT 23:22so i had this thing happen where i got switched in the hospital and then the pharmacy gave me the old one and i took both for like 3 days?? i thought i was having side effects but it was just… double dose?? 😅 i started writing everything down after that. also, i just tell my pharmacist ‘hey, i was in the hospital last week’ and they always check. it’s not weird. it’s smart.

Taylor Mead

March 2, 2026 AT 03:39This whole thing is wild - and honestly, kinda beautiful. Two systems, two philosophies. One’s about money. One’s about survival. The fact they don’t talk isn’t an accident - it’s a design flaw. But the fact that we’re even talking about it? That’s progress. I’ve seen pharmacists go out of their way to call a hospital pharmacy just to confirm a med change. Those are the real heroes. We need more of that. Not more rules. More connection.