When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $500 bill for a brand-name pill, it’s easy to assume everything here is outrageously expensive. But here’s the twist: the generic version of that same drug? It’s often cheaper than in Canada, Germany, or Japan. The U.S. doesn’t just have high drug prices - it has a split personality when it comes to what you pay for medicine.

Generics in the U.S. Are Actually Cheaper Than Almost Everywhere Else

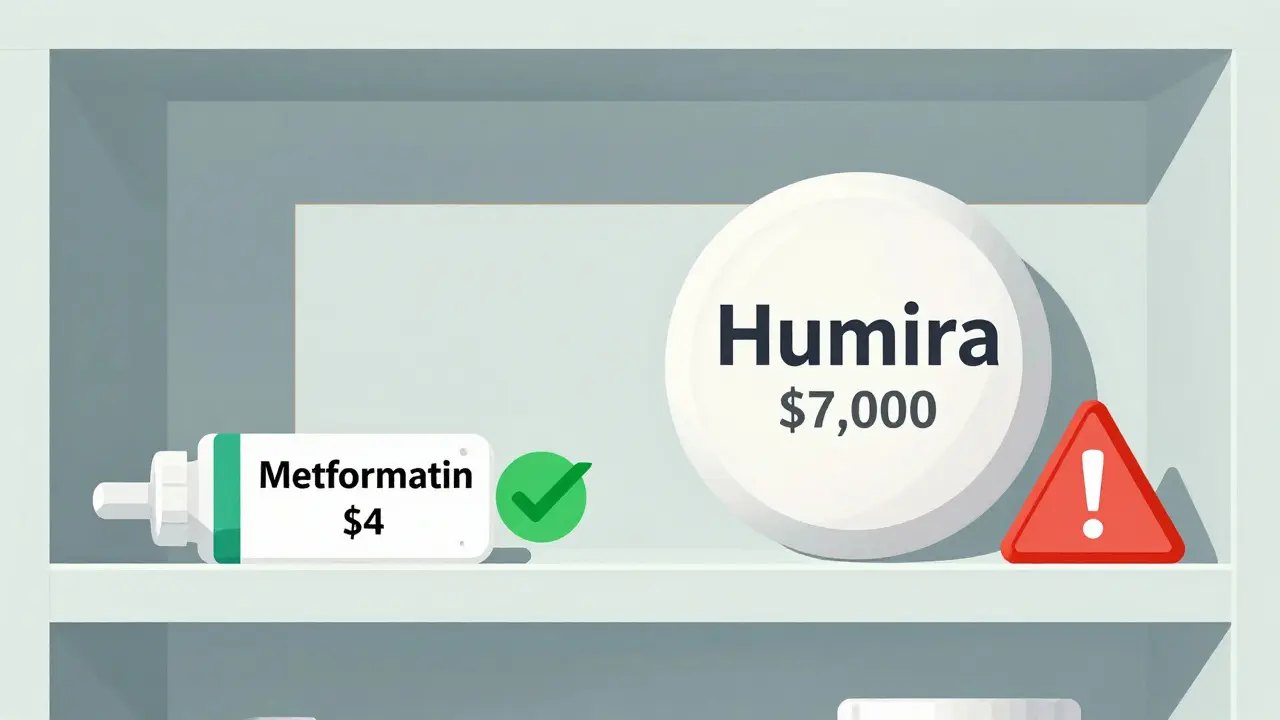

Most people don’t realize that 9 out of 10 prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. And here’s the surprising part: those generics cost, on average, 33% less than they do in other developed countries. A 2022 study by the RAND Corporation found that while brand-name drugs in the U.S. cost more than four times what they do abroad, generic prices were lower across the board. For example, a 30-day supply of generic metformin - used for type 2 diabetes - costs around $4 in the U.S. In the U.K., it’s closer to $8. In France, it’s $10. Even in Canada, where people often assume prices are lower, generic metformin runs about $6.

Why? It’s not magic. It’s volume and competition. The U.S. market buys more generic drugs than any other country. That gives pharmacies and insurers massive leverage. When three or more companies start making the same generic drug, prices crash. According to the FDA, once three competitors enter the market, the price drops to just 15-20% of the original brand-name price. That’s why you can get 90-day supplies of common generics like lisinopril or atorvastatin for under $10 at Walmart or Costco - sometimes even less.

Brand-Name Drugs Are Where the Real Price Shock Happens

But here’s where things get ugly. While generics are cheap, brand-name drugs are the opposite. The same RAND study found U.S. prices for brand-name medications are 308% higher than in other OECD countries. For newer, high-demand drugs like Jardiance (for diabetes) or Stelara (for psoriasis), the U.S. price can be three to four times what it is in Australia or Japan. Medicare’s first negotiated prices for these drugs still came in at 2.8 times the global average.

Why? Because the U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices like most other countries. In places like Germany or France, the government sets a maximum price before a drug even hits the market. In the U.S., manufacturers can set any price they want - and they do. The result? A patient on a brand-name drug like Humira might pay $7,000 a month in the U.S., while the same drug costs under $1,000 in the U.K. and under $2,000 in Canada. That’s not a pricing difference - it’s a financial chasm.

The Rebate System Hides the Real Cost

Here’s where it gets even more confusing. If you look at the list price - the sticker price on the box - U.S. drug prices look insane. But that’s not what most people actually pay. The U.S. system runs on rebates. Pharmacies, insurers, and government programs like Medicare negotiate deep discounts behind the scenes. A drug might list for $1,000, but after rebates, the net price is $500. And here’s the kicker: a 2024 University of Chicago study found that when you factor in these rebates, the U.S. actually pays less than other countries for the same drugs - especially for generics.

That’s because the U.S. has a unique system: insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) demand rebates from drugmakers in exchange for putting their drugs on preferred lists. In countries like Canada or the U.K., the government just says, “This is what we’ll pay,” and the drugmaker either accepts it or doesn’t sell there. In the U.S., the drugmaker can charge more upfront - but then has to give back a big chunk. The result? Lower net prices for public programs, but higher list prices that confuse consumers and fuel outrage.

Why Do Other Countries Pay Less? It’s Not Just Government Control

Many assume the U.S. is the only country that doesn’t control drug prices. But that’s not entirely true. Countries like Germany and Japan don’t set prices by fiat - they negotiate. And they use one powerful tool: they threaten to block access. If a drugmaker won’t lower its price, those countries simply won’t cover it. That’s why Japan and France consistently have the lowest prices in the OECD. They don’t just ask - they walk away.

The U.S. didn’t have that power - until recently. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 gave Medicare the ability to negotiate prices for the most expensive drugs. In 2024, the first 10 drugs were selected. But even those negotiated prices were still higher than international benchmarks. For example, Medicare’s price for Jardiance was $204 per month. The average in 11 other countries? $52. That’s nearly four times higher. So even when the U.S. tries to negotiate, it’s still paying more.

What About Generic Shortages and Price Spikes?

Don’t get fooled by the low average. Sometimes, generics get expensive - and fast. When only one or two companies make a drug, they can raise prices without fear of competition. That’s what happened with doxycycline, a common antibiotic. When only one manufacturer was left, the price jumped from $20 to $1,800 per bottle. The FDA has documented over 100 cases like this since 2015. The problem isn’t the system - it’s the lack of competition. When a company shuts down production or exits the market, prices spike. That’s why the FDA now tracks “single-source” generics and pushes for new manufacturers to enter.

That’s also why some generics are still expensive - not because the U.S. is bad at pricing, but because the market broke. The fix? More generic manufacturers. The FDA approved 773 new generic drugs in 2023. That’s expected to save $13.5 billion in the next few years. More competition = lower prices. Simple math.

What Does This Mean for You?

If you’re taking a generic drug, you’re probably getting one of the best deals in the world. You’re paying less than 90% of other countries for the same medicine. Use mail-order pharmacies, shop at Costco or Walmart, and always ask if a generic is available. You’ll save hundreds - sometimes thousands - a year.

If you’re on a brand-name drug, you’re in the 10% that pays the price for the other 90%. That’s where the real cost burden lies. Talk to your doctor about alternatives. Ask if there’s a biosimilar (a cheaper version of a biologic drug). Check patient assistance programs from drugmakers. And if you’re on Medicare, know that more drugs will be negotiated in 2025 - potentially lowering your costs.

The myth that “everything is more expensive in America” is only half true. For generics? You’re winning. For brand names? You’re being asked to pay more than anyone else - and you’re paying for innovation worldwide. That’s the ugly truth behind the numbers.

What’s Next for Drug Pricing?

The next round of Medicare-negotiated drugs is due out in February 2025. That could mean lower prices for more people. But the pharmaceutical industry is pushing back hard, arguing that lower U.S. prices will hurt global R&D. The truth? The U.S. funds most of the world’s new drug development. Countries that pay less benefit from that investment. That’s why some experts say the U.S. model - high brand prices, low generics - might be the only way to keep innovation alive.

But that doesn’t mean we have to accept $10,000-a-month prices for drugs that cost $500 elsewhere. The real solution? More generic competition. Faster FDA approvals. And smarter negotiation - not just for Medicare, but for all public programs. Until then, know this: if you’re on a generic, you’re getting a bargain. If you’re on a brand, you’re paying the bill for the whole system.

Jarrod Flesch

January 22, 2026 AT 06:17Wow, I never realized generics in the U.S. were this cheap compared to Australia. I pay like $12 for metformin here, and I thought that was normal. Turns out I’ve been overpaying this whole time 😅

Barbara Mahone

January 22, 2026 AT 19:04The rebate system is such a black box. People see the list price and freak out, but the net price? Often way lower. It’s not transparency-it’s theater.

Kelly McRainey Moore

January 23, 2026 AT 20:16My grandma gets her lisinopril for $3 at Walmart every 90 days. She says it’s the only thing keeping her sane. I’m so glad we’ve got that option.

Amber Lane

January 25, 2026 AT 04:28Generics are a win. Brand names? Not so much.

Ashok Sakra

January 27, 2026 AT 01:11THEY’RE LYING TO US!!! The pharma companies are working with the government to keep us sick so they can make more money!! I know someone who died because they couldn’t afford insulin!!

michelle Brownsea

January 27, 2026 AT 13:04Let’s be clear: the fact that we pay more for brand-name drugs is not a flaw-it’s a feature. Innovation doesn’t fund itself. If we don’t pay the premium, who will? The Germans? The Japanese? They’re free-riding on American R&D-and now they want to cap prices? Unacceptable.

Malvina Tomja

January 29, 2026 AT 12:49Ugh. Another ‘U.S. is weird’ article. Look, if you’re on a brand-name drug and you’re paying $7k/month, you’re either not trying hard enough or you’re being scammed by your own doctor. Ask for the generic. Ask for the coupon. Ask for the patient program. Stop being a victim. You have options.

Samuel Mendoza

January 31, 2026 AT 03:39Actually, Canada’s generics aren’t $6. They’re $8. You’re wrong.

Steve Hesketh

February 1, 2026 AT 02:34Bro, this is why I love America-real talk. You got cheap generics for the people who need it, and the big pharma pays for the future cures. We’re not perfect, but we’re building the future while others just sit back and take. Respect.

shubham rathee

February 2, 2026 AT 22:25the whole thing is a scam the fda approves generics but then the big companies buy up the small ones so no one can compete and then they jack up the price and no one talks about this

Sangeeta Isaac

February 4, 2026 AT 09:06So let me get this straight… I’m paying less than everyone else for my blood pressure med, but I’m still mad because my friend’s Humira costs $7k? Like… I’m winning the lottery and still crying about the fact that someone else got a yacht? 😂

Philip Williams

February 6, 2026 AT 06:28It is imperative to recognize that the structural dynamics of pharmaceutical pricing in the United States are uniquely complex. The interplay between market volume, regulatory non-intervention, and rebate-based negotiations creates a bifurcated system wherein consumer perception is systematically misaligned with economic reality.

Melanie Pearson

February 8, 2026 AT 04:59Let’s not pretend this is about ‘innovation.’ This is about corporate greed disguised as patriotism. We are the only country that allows drugmakers to charge whatever they want. That’s not capitalism. That’s extortion.

Rod Wheatley

February 8, 2026 AT 21:38THIS IS SO IMPORTANT!! If you’re on a brand-name drug, DO NOT GIVE UP. Talk to your pharmacist. Check GoodRx. Ask for samples. There are programs out there. You’re not alone. I helped my neighbor cut her insulin bill from $800 to $30. It’s possible!!

Jerry Rodrigues

February 10, 2026 AT 10:05Generics are cheap. Brands are expensive. That’s the system. Don’t hate the player, hate the game.