Quick Takeaway

- Massage therapy uses pressure, stretch, and movement to improve blood flow and reduce muscle tension.

- It complements physiotherapy for sports injuries, chronic pain, and post‑operative rehab.

- Evidence shows measurable reductions in inflammation markers and pain scores.

- Choosing the right technique-Swedish, Deep Tissue, Myofascial Release, or Trigger Point-depends on the condition.

- Integrating regular sessions with home self‑care maximizes long‑term benefits.

Massage Therapy is a hands‑on treatment that manipulates soft tissues to improve function and alleviate pain. It has moved from spa luxury to a clinical tool for managing skeletal muscle conditions, which include strains, myofascial pain syndrome, tendinopathies, and chronic low‑back discomfort.

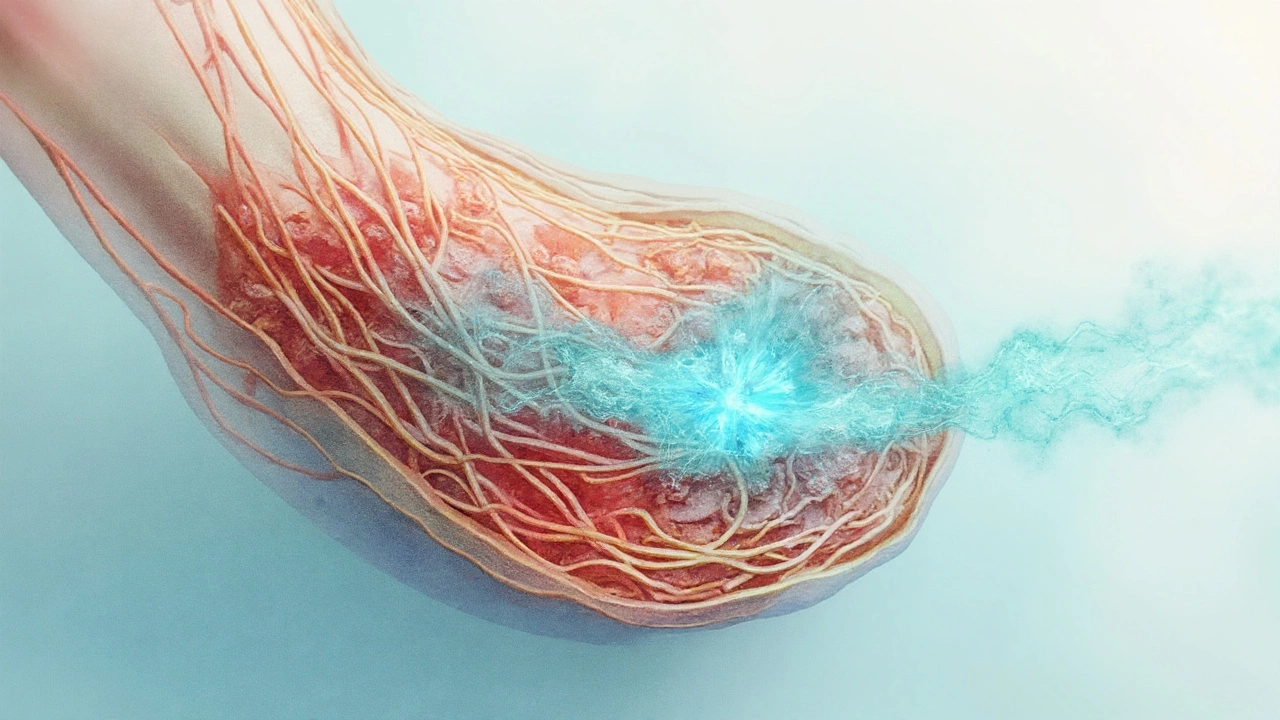

How Massage Works on Muscles

Three physiological pathways explain why Massage Therapy works:

- Circulatory boost: Mechanical pressure enhances venous return, increasing oxygen delivery and waste removal.

- Neuromodulation: Stretching of mechanoreceptors triggers the release of endorphins and reduces sympathetic tone.

- Fascial remodeling: Targeted force realigns collagen fibers, decreasing adhesions that restrict motion.

These effects lower inflammation levels, as measured by reduced C‑reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin‑6 in several clinical trials.

Common Skeletal Muscle Conditions Treated

Therapists often face a predictable set of problems:

- Myofascial Pain Syndrome - tight knots called trigger points that radiate pain.

- Hamstring Strain - common in runners and sprinters.

- Patellar Tendinopathy - “jumper’s knee” seen in basketball and volleyball.

- Chronic Low Back Pain - often linked to poor core stability.

In each case, the therapist tailors pressure depth, stroke speed, and patient positioning to address the underlying dysfunction.

Massage Techniques Compared

| Technique | Pressure Level | Primary Goal | Typical Session (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swedish | Light‑to‑moderate | Relaxation & circulation | 45‑60 |

| Deep Tissue | Moderate‑to‑high | Break down adhesions | 30‑45 |

| Myofascial Release | Low‑to‑moderate (sustained) | Re‑align fascial planes | 60‑90 |

| Trigger Point | High (localized) | Deactivate knots | 20‑30 |

The right technique depends on the condition. For acute strains, Swedish or gentle Myofascial Release eases pain without aggravating tissue. Chronic tendinopathies often benefit from Deep Tissue and Trigger Point work to remodel scar tissue.

Integrating Massage with Physiotherapy

Massage is not a stand‑alone cure; it shines when blended with active rehab. A typical pathway looks like this:

- Initial assessment by a physiotherapist to identify movement deficits.

- Targeted massage sessions to reduce pain and improve tissue extensibility.

- Progressive therapeutic exercises (strengthening, proprioception) once range of motion returns.

- Maintenance massage every 2‑4 weeks to prevent re‑injury.

Studies in athletic populations show a 15‑20% faster return‑to‑play when this combined approach is used.

Evidence and Clinical Guidelines

Major health bodies now reference massage as an adjunct therapy:

- The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) includes massage in its post‑exercise recovery recommendations.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) cites moderate‑quality evidence for massage in chronic low‑back pain.

- Systematic reviews in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy report average pain‑score reductions of 2.5 points on a 10‑point scale.

While the evidence is strongest for Myofascial Release and Trigger Point therapy in myofascial pain, even light Swedish techniques provide measurable improvements in blood flow, as shown by Doppler ultrasound studies.

Practical Tips for Patients and Therapists

For clinicians:

- Document pressure level using a 0‑10 scale; adjust based on patient feedback.

- Combine manual work with patient‑education on stretching and hydration.

- Screen for contraindications: recent fractures, deep vein thrombosis, severe skin infections.

For patients:

- Communicate any tingling or sharp pain immediately - it may signal nerve irritation.

- Stay hydrated after each session to help flush out metabolic waste.

- Incorporate gentle home self‑myofascial release with a foam roller 2‑3 times weekly.

When done correctly, Massage Therapy can speed recovery, improve functional range, and lower the reliance on pain medication.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Massage sits within a broader pain‑management ecosystem. Topics worth exploring next include:

- neuromuscular electrical stimulation - a modality that complements manual work.

- cryotherapy - useful for acute inflammation before massage.

- functional movement screening - helps identify patterns that lead to muscle overuse.

Reading about these will give a 360° view of how to keep muscles healthy and resilient.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can massage replace physiotherapy for muscle injuries?

Massage is an excellent adjunct, but it does not replace the active, corrective exercises that physiotherapy provides. The best outcomes come from a combined plan.

How often should I receive massage for chronic low‑back pain?

Most clinicians recommend 1‑2 sessions per week for the first 4‑6 weeks, then taper to maintenance every 2‑4 weeks based on pain levels and functional gains.

Is deep‑tissue massage safe after a recent muscle strain?

During the acute inflammation phase, high pressure can aggravate the injury. Light Swedish or gentle Myofascial Release is preferred until swelling subsides (typically 48‑72hours).

What objective measures show massage effectiveness?

Researchers track pain‑numeric rating scales, range‑of‑motion goniometry, and biomarkers like CRP or IL‑6. Ultrasound Doppler also shows increased blood flow post‑session.

Can self‑myofascial release replace professional massage?

Self‑tools are great for maintenance, but they lack the nuanced feedback a trained therapist provides. Use them as a supplement, not a substitute.

Dalton Hackett

September 25, 2025 AT 16:53Massage therapy has evolved far beyond the realm of mere luxury spa treatments, becoming a cornerstone in modern musculoskeletal rehabilitation. The physiological mechanisms-enhanced circulatory flow, neuromodulation via mechanoreceptor stimulation, and fascial remodeling-operate in concert to alleviate pain and restore function. Clinical studies consistently demonstrate reductions in inflammatory biomarkers such as CRP and interleukin‑6 after a series of targeted sessions. When integrated with physiotherapy, the combined approach shortens recovery timelines by approximately fifteen to twenty percent, a figure that is both statistically and practically significant. The choice of technique is critical; Swedish massage offers light‑to‑moderate pressure ideal for acute inflammation, whereas deep‑tissue work excels at breaking down chronic adhesions. Myofascial release, with its sustained low‑to‑moderate pressure, specifically targets fascial planes to realign collagen fibers and reduce restrictive knots. Trigger point therapy, employing high localized pressure, deactivates hyperirritable spots that radiate pain throughout the muscle. For athletes dealing with jumper's knee or hamstring strains, a strategic mix of deep‑tissue and trigger point modalities can remodel scar tissue more effectively than either technique alone. Moreover, regular massage sessions promote tissue extensibility, which in turn facilitates more efficient execution of therapeutic exercises prescribed by physiotherapists. Hydration post‑session is essential; increased fluid intake helps flush metabolic waste that has been mobilized during the treatment. Patients are advised to communicate any tingling or sharp sensations immediately, as these may indicate nerve irritation that requires adjustment of technique. Documentation of pressure levels on a 0‑10 scale ensures consistency across sessions and allows therapists to refine their approach based on patient feedback. Contraindications such as recent fractures, deep vein thrombosis, or severe skin infections must be meticulously screened to prevent adverse outcomes. While self‑myofascial tools like foam rollers are valuable for maintenance, they lack the nuanced feedback provided by a trained therapist and should therefore complement, not replace, professional care. The body of evidence, ranging from randomized controlled trials to systematic reviews, supports the adjunctive role of massage in managing chronic low‑back pain, myofascial pain syndrome, and tendinopathies. In sum, when applied judiciously and in concert with active rehabilitation strategies, massage therapy can significantly enhance recovery, improve functional range of motion, and reduce reliance on analgesic medications.

William Lawrence

September 26, 2025 AT 20:40Oh great, because nothing says "professional rehab" like a 60‑minute flirt with your therapist’s hands.

Grace Shaw

September 28, 2025 AT 00:27While the article provides a thorough overview of massage modalities, it is imperative to underscore the necessity of evidence‑based practice when integrating such interventions into a comprehensive treatment plan. The practitioner must assess the individual’s clinical presentation, comorbidities, and therapeutic goals before selecting a specific technique, thereby ensuring alignment with established guidelines. Moreover, documentation of treatment parameters, including pressure intensity and duration, fosters continuity of care among multidisciplinary teams.

Sean Powell

September 29, 2025 AT 04:13Yo, good points on the guidelines

just remember to keep the vibe inclusive – everyone’s body speaks a diff language so mix up the strokes and stay chill

Henry Clay

September 30, 2025 AT 08:00Statistically speaking the reduction in pain scores is real not just hype : ) the data shows a mean drop of 2.5 on a ten point scale which is clinically meaningful especially when you factor in the lowered need for opioids

Isha Khullar

October 1, 2025 AT 11:47Ah the dance of flesh and force! One must contemplate the metaphysical echo of each knead, for in the press of a therapist’s palm lies the transient poetry of relief – even if occasional typo slips in our hurried notes, the essence remains unblemished.

Lila Tyas

October 2, 2025 AT 15:33Hey everyone! If you’re feeling stuck with nagging muscle pain, give massage a try and pair it with some light stretching – you’ll be amazed at how quickly the tightness melts away. Keep moving and stay positive!

Mark Szwarc

October 3, 2025 AT 19:20To add to Lila’s encouragement, it’s beneficial to schedule a brief consultation with a certified massage therapist to tailor the session to your specific injury. Proper technique selection can accelerate tissue healing and improve functional outcomes.

BLAKE LUND

October 4, 2025 AT 23:07Picture this: a symphony of strokes, each note resonating through fibers like a vibrant mural of movement. When the therapist weaves together Swedish lullabies with deep‑tissue crescendos, the body responds in technicolor.

Veronica Rodriguez

October 6, 2025 AT 02:53Great analogy, Blake! 😊 For anyone curious, starting with a 30‑minute session and gradually increasing to 60 minutes can help the body adapt safely. 🌟

Holly Hayes

October 7, 2025 AT 06:40Honestly, the whole "massage as therapy" narrative feels a bit overhyped – it's just good old pressure, nothing more sophisticated than a decent rubdown.