Levodopa Protein Timing Calculator

Daily Protein Calculator

Optimize levodopa effectiveness by distributing protein correctly throughout your day

Your Optimal Plan

For people with Parkinson’s disease taking levodopa, what’s on your plate can make or break your day. It’s not just about feeling full or eating healthy - it’s about whether you’ll be able to walk, stand, or even hold a cup of coffee without shaking. The reason? Levodopa, the gold-standard medication for Parkinson’s, doesn’t just compete with disease - it competes with your breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Why Protein Ruins Your Levodopa

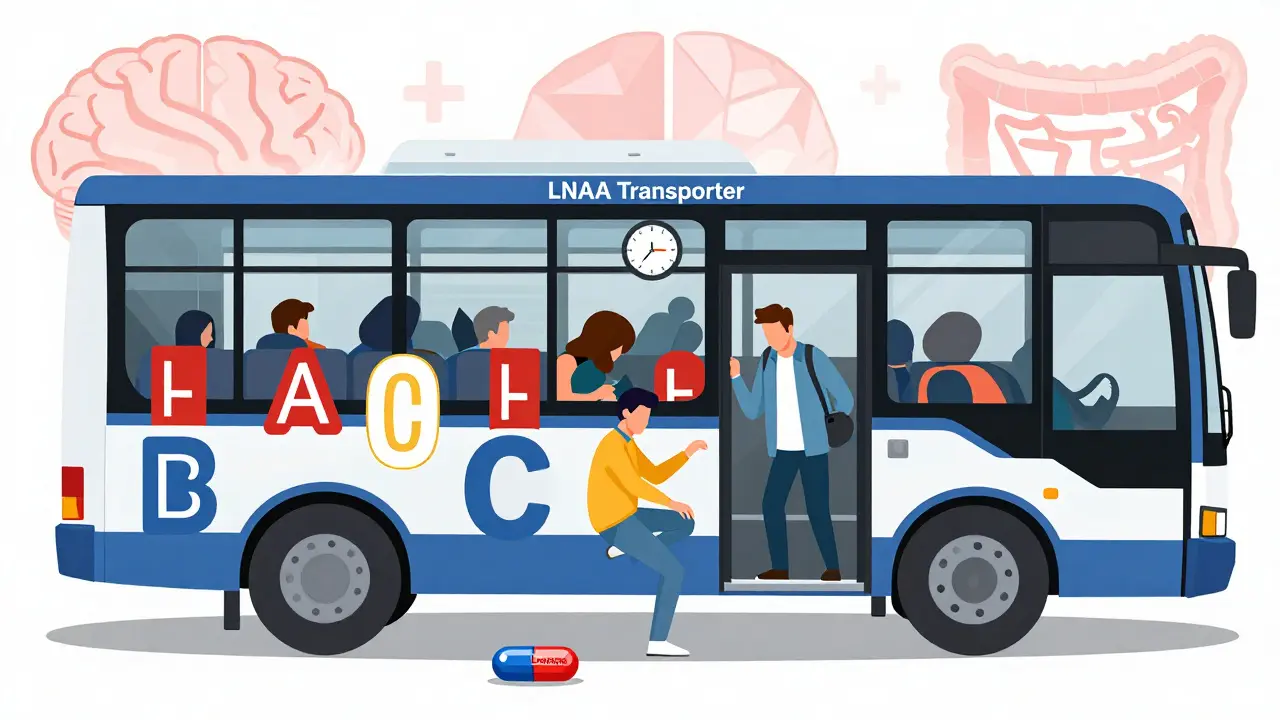

Levodopa doesn’t slip into your brain like a key into a lock. It has to ride a crowded bus called the LNAA transporter. That’s short for large neutral amino acid transporter. And guess who else is on that bus? Every single amino acid from the meat, eggs, beans, and dairy you eat. Leucine, isoleucine, valine, phenylalanine - they all want the same ride. And they’re louder, bigger, and show up in greater numbers than levodopa ever could. When you eat a high-protein meal - say, a 30-gram serving of chicken or a big bowl of lentils - those amino acids flood your bloodstream within an hour. Their concentration spikes by 30-50%. That’s enough to block up to 40% of levodopa from getting absorbed in your gut. Even worse, once levodopa finally makes it into your blood, those amino acids are waiting at the blood-brain barrier to block it again. The result? Your meds don’t work when you need them most. Studies show this isn’t rare. About half of people on long-term levodopa therapy - usually after 8-13 years - start having unpredictable ‘off’ periods. These are times when movement suddenly shuts down, even though they took their pill. One study found that eating a high-protein lunch could increase ‘off’ time by up to 79% compared to low-protein meals. That’s not just inconvenient - it’s dangerous. Falls, freezing, and loss of independence follow.Three Ways to Fight Back

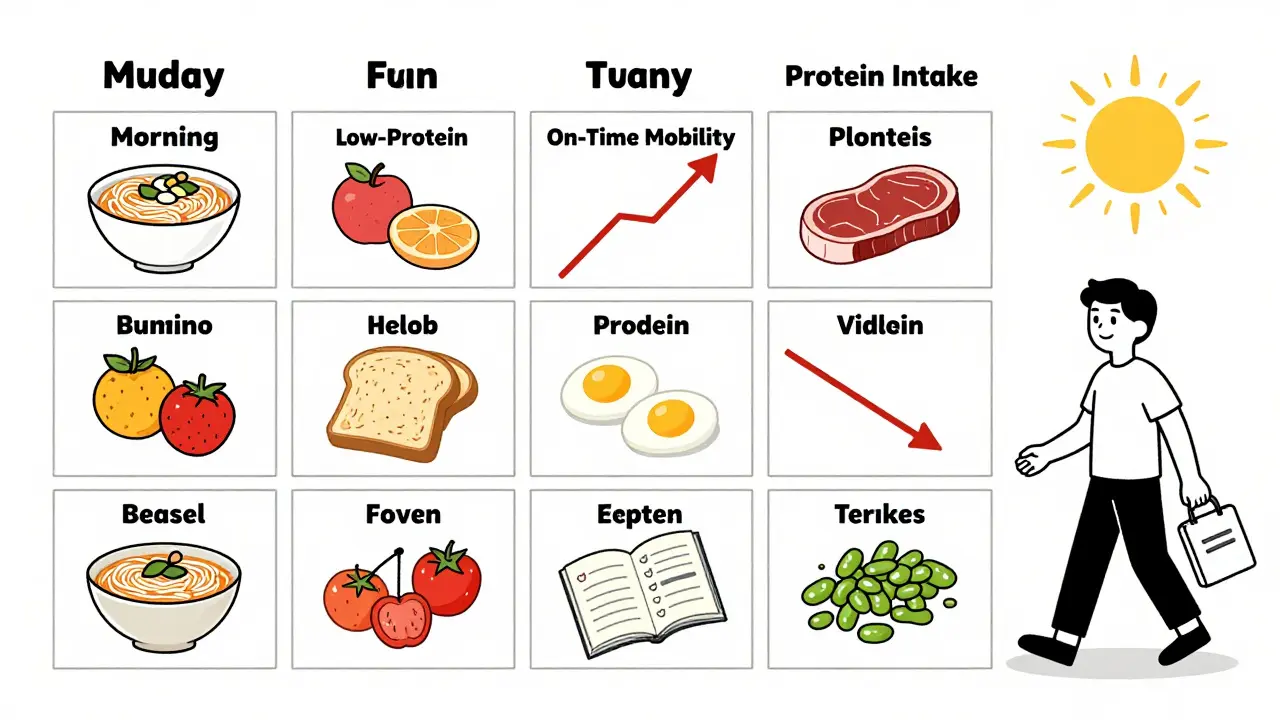

You don’t have to give up protein forever. But you do need to change when and how you eat it. Three strategies have been tested and proven in clinical settings.- Low Protein Diet (LPD): Cut total daily protein to 40-50 grams. That’s about the amount in two eggs, a small chicken breast, and a cup of beans. Sounds simple? It’s not. Most people eat 80-100 grams a day. Cutting that in half means saying no to most meats, dairy, and legumes. And it’s hard to do without getting weak or losing weight.

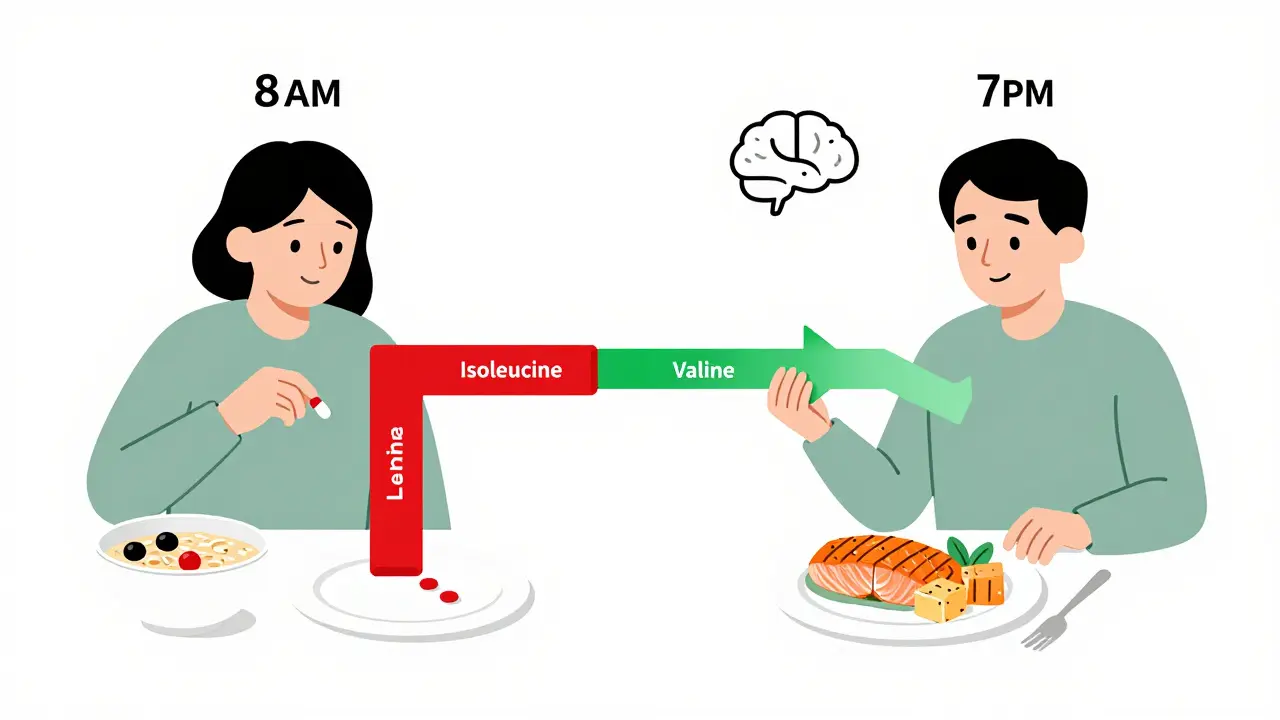

- Protein Redistribution Diet (PRD): This is the most effective method. Eat almost all your protein - 80-85% - in the evening. Keep daytime meals under 7 grams. That means breakfast and lunch become low-protein: oatmeal with fruit, rice noodles, vegetables, and fruit smoothies. Dinner gets the steak, the salmon, the tofu. Why does this work? Because levodopa works best during the day when you need to move. At night, when you’re sleeping, your body doesn’t need as much motor control. So you sacrifice protein at the wrong time to gain movement at the right time.

- Low-Protein Products (LPP): These are specialty foods - low-protein bread, pasta, and flour - designed to help you eat more without the amino acid overload. They’re available in Europe and parts of North America, but expensive and hard to find. Only 22% of users say they make a real difference in how they feel about their diet.

PRD wins. Research from Barichella and colleagues showed that people on PRD gained back over an hour and a half of ‘on’ time each day - time when they could walk, talk, and move without freezing. That’s more than LPD. More than timing pills alone. More than any other dietary trick.

Timing Your Pills Right

Some people try taking levodopa 30-60 minutes before meals. It sounds logical. But it doesn’t always work. Why? Because if your stomach is empty, the pill might pass through too fast - before it’s fully absorbed. Or, if you’re nauseous (a common side effect), you might vomit it up. And if you’ve got delayed gastric emptying - common in advanced Parkinson’s - the pill sits there for hours, useless. The best timing? Try 45 minutes before eating. Not 15. Not 90. Forty-five. That’s the sweet spot for most people. And if you’re still having trouble, try this: eat a small, low-protein snack - like a banana or a few crackers - 15 minutes before your pill. It helps settle your stomach without blocking absorption.

Who Needs This? Who Doesn’t?

Not everyone with Parkinson’s has this problem. Only 40-50% of patients on levodopa experience noticeable protein interference. That means half of you can eat steak and not feel a thing. So don’t start restricting protein just because you read this. Look for signs: Do you notice your meds work better in the morning? Do you get worse after lunch? Do you feel ‘off’ even though you took your pill on time? If yes, you’re likely one of the people who benefit from protein timing. Also, don’t do this if you’re underweight. If your BMI is below 20, cutting protein could make you weaker, not stronger. And if you’re already losing weight, adding protein restriction could push you into malnutrition. That’s worse than tremors.The Real Problem: Sticking With It

Here’s the hard truth: 68% of people who try PRD quit within a year. Why? Because food is culture. It’s family. It’s comfort. It’s Sunday roast, birthday cake, and shared meals with friends. One Reddit user, u/ParkinsonsWarrior, said after switching to PRD: “I gained 2.5 hours of reliable mobility every day.” But he also said, “I haven’t eaten a burger in 14 months.” People report social isolation. They skip dinners. They avoid holidays. They feel like they’re on a diet no one else understands. And that’s why the most successful programs aren’t about rules - they’re about flexibility. The trick? One high-protein meal a day - at night. That’s called a “protein holiday.” It’s not perfect, but it’s doable. And it’s better than nothing.What Experts Say

Dr. Carley Rusch, a registered dietitian specializing in Parkinson’s, puts it bluntly: “There’s no one-size-fits-all. You have to tailor this to the person.” That means:- Work with a dietitian who knows Parkinson’s - not just any nutritionist.

- Track your food and symptoms in a journal for 2-3 weeks. Note what you ate, when you took your pill, and how you felt an hour later.

- Try PRD for 4-6 weeks. If you don’t see improvement, stop. It’s not for everyone.

- Don’t cut protein if you’re losing weight. Adjust your levodopa dose instead.

Studies show that people who get professional help - a dietitian, a neurologist, a pharmacist - are 78% more likely to improve their symptoms than those who try alone.

Watch Out for Hidden Risks

Restricting protein doesn’t just mean fewer steaks. It means fewer vitamins too. Long-term low-protein diets can lead to deficiencies in vitamin B12, iron, and zinc. That’s why blood tests are essential. Check every 6 months. Also, some people reduce their levodopa dose when they start PRD - sometimes by 15-25%. That’s because their body absorbs the drug better. But never adjust your dose without talking to your doctor. Too little levodopa means more ‘off’ time. Too much can cause dyskinesia - uncontrollable movements.What’s Next?

The future is looking smarter. Researchers are testing something called “protein pacing” - tiny amounts of protein spread evenly through the day. Early trials show it improves adherence and keeps amino acid levels steady, so levodopa doesn’t get blocked. It’s in Phase II trials now, and if it works, it could change everything. There’s also new tech: wearable sensors that track amino acid levels in real time. Imagine a device that tells you, “Your leucine is high. Wait 40 minutes before your next pill.” That’s not science fiction anymore.Practical Tips You Can Start Today

- Take levodopa 45 minutes before breakfast - and eat a low-protein breakfast (oatmeal, toast, fruit).

- Use MyFitnessPal or another app to track protein. Aim for under 7g per meal during the day.

- Swap chicken for rice noodles. Swap cheese for fruit yogurt. Swap beans for mashed potatoes.

- Save your protein for dinner - steak, salmon, tofu, eggs.

- Keep a journal: food, time, pill, symptoms. Look for patterns.

- Ask your doctor for a referral to a dietitian who works with Parkinson’s patients.

This isn’t about being perfect. It’s about getting back control. One meal at a time.

Does eating protein stop levodopa from working completely?

No, it doesn’t stop it completely - but it can reduce absorption by 25-40% and delay when it starts working by 45-90 minutes. That’s enough to cause noticeable ‘off’ periods, especially in advanced Parkinson’s. The effect is dose-dependent: meals with over 10 grams of protein start to interfere, and meals over 20 grams cause major drops in effectiveness.

Can I just take more levodopa instead of changing my diet?

Increasing your dose might seem like an easy fix, but it often makes things worse. Higher doses increase the risk of dyskinesia - involuntary movements - and don’t always solve the timing problem. The real issue isn’t how much levodopa you take, but how much reaches your brain. Protein blocks absorption, so more pills won’t help if they’re blocked at the gut or blood-brain barrier.

Is a low-protein diet safe for long-term use?

Only if carefully monitored. Long-term low-protein diets can lead to muscle loss, weight loss, and deficiencies in vitamin B12, iron, and zinc. People with Parkinson’s are already at higher risk for these issues. Never restrict protein below 0.6g per kg of body weight without medical supervision. If you’re underweight (BMI <20), avoid protein restriction entirely.

What’s the difference between PRD and a low-protein diet?

A low-protein diet cuts total protein every day. PRD keeps your total protein the same - just moves 80-85% of it to dinner. That means you still get enough protein to stay healthy, but you avoid interfering with levodopa during the day when you need it most. PRD is more effective than strict low-protein diets and easier to stick with long-term.

Do I need to buy special low-protein foods?

No, you don’t. You can manage PRD with regular foods - rice, pasta, vegetables, fruits, and bread. Low-protein specialty products (like special flour or pasta) help some people stick with the plan, but only 22% say they make a big difference. Focus on swapping high-protein foods for low-protein ones first. A cup of rice has less than 3g of protein. A chicken breast has 25g. That’s the real swap.

How long does it take to see results from protein redistribution?

Most people notice improvement in 2-4 weeks. But full adaptation - learning what to eat, when to take pills, how to plan meals - can take 2-3 months. The key is consistency. Keep a food and symptom journal. If you don’t see better ‘on’ time after 6 weeks, talk to your doctor. It might not be the protein - or you might need help adjusting your medication.

Can I still eat dairy and eggs on a protein redistribution diet?

Yes - but not during the day. Eggs and dairy are high in protein. One egg has about 6g. One cup of milk has 8g. So save them for dinner. You can have a small amount of cheese or yogurt in the evening. Avoid them at breakfast and lunch. Use non-dairy alternatives like rice milk or oat milk if you need to reduce protein further.

Is this interaction the same for all Parkinson’s medications?

No. This problem is specific to levodopa because it uses the same transporter as amino acids. Other Parkinson’s drugs - like dopamine agonists (ropinirole, pramipexole), MAO-B inhibitors (selegiline), or COMT inhibitors (entacapone) - don’t compete with dietary protein. So if you’re on one of those, protein won’t interfere. But if you’re on levodopa - even in combination - protein still matters.

Sarah Triphahn

January 13, 2026 AT 16:31Wow. So you're telling me I have to give up my chicken salad to walk better? Thanks for the life update, doctor.

Guess I'll just stay frozen and call it 'natural aging'.

Vicky Zhang

January 14, 2026 AT 07:15I just want to hug every single person reading this who’s struggling with this.

You’re not alone. I’ve been there - crying in the grocery store because I couldn’t figure out what to buy.

But I tried PRD for 6 weeks and now I can pick up my grandkids without shaking.

It’s not easy. It’s not glamorous.

But it’s worth it.

Start small. One low-protein breakfast. One meal at a time.

You’ve got this. I believe in you.

And if you need someone to vent to? I’m here.

Always.

Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 15, 2026 AT 05:45This is all Big Pharma’s fault.

They made levodopa to work poorly so you’d keep buying it.

And now they’re selling you ‘low-protein bread’ for $12 a loaf to keep you hooked.

Real doctors don’t care about your diet - they care about your paycheck.

Try fasting. Or just stop taking it. Your body will heal itself.

They don’t want you to know this.

But now you do.

Henry Sy

January 15, 2026 AT 09:27Man, I used to eat a whole damn rotisserie chicken for lunch and wonder why I couldn’t button my shirt.

Turns out, my body wasn’t broken - my plate was.

Switched to PRD. Ate my steak at 8 PM. Slept like a baby.

Woke up able to walk to the fridge without looking like a marionette.

Now I’m the weirdo at family dinners, picking at rice and carrots while everyone else digs into ribs.

Worth it.

Also, I miss burgers.

But I miss falling less.

So yeah.

Do the thing.

Anna Hunger

January 16, 2026 AT 17:21It is imperative to underscore that the Protein Redistribution Diet (PRD) is not a dietary fad, but a clinically validated, evidence-based intervention supported by peer-reviewed literature from Barichella et al. (2018) and subsequent meta-analyses.

Furthermore, adherence to this protocol requires meticulous tracking of macronutrient intake, ideally via digital food diaries with verified nutritional databases.

It is also strongly recommended that patients consult with a registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) specializing in movement disorders prior to implementation, as individual metabolic profiles vary significantly.

Failure to do so may result in unintended catabolic states or nutrient deficiencies, particularly in elderly populations with reduced renal clearance.

Thus, while the concept is straightforward, its execution demands rigor, discipline, and professional oversight.

Jason Yan

January 17, 2026 AT 12:05It’s funny, isn’t it? We spend so much time trying to fix our brains with pills, but the real answer’s on our plates.

Levodopa isn’t broken - it’s just outnumbered.

Like showing up to a party in a tuxedo while everyone else is in hoodies.

You’re not the problem. You’re just outgunned.

And the solution isn’t more pills.

It’s timing.

It’s strategy.

It’s choosing when to fight and when to let go.

Maybe that’s the real lesson here - not just about Parkinson’s, but about life.

Some battles you win by changing the battlefield, not by bringing more soldiers.

PRD isn’t a diet.

It’s a dance with your own body.

And for some of us? It’s the only way to keep dancing.

shiv singh

January 19, 2026 AT 00:50You people are so obsessed with your protein.

Back home in India, we eat dal and rice every day and still walk fine.

Why? Because we don’t eat meat like animals.

You Americans think food is medicine - we know food is culture.

And culture doesn’t need your fancy diets.

Just eat like your grandparents did.

Simple. Real.

Not this low-protein bread nonsense.

You’re overcomplicating life.

And now you’re scared to eat dinner with your family.

That’s the real disease.

Robert Way

January 19, 2026 AT 15:11so i tried the 45 min thing and it kinda worked but then i ate a banana before and it made me feel weird like my head was spinning

also i dont know if i should be eating eggs at night or if theyre bad idk

my wife says i should just stop taking the pills

she says god will heal me

idk man

help

Allison Deming

January 21, 2026 AT 04:45It is deeply concerning that the article promotes a dietary intervention without adequately addressing the psychosocial implications of long-term food restriction.

For individuals with Parkinson’s, social isolation is already a leading contributor to depression and accelerated cognitive decline.

Requiring patients to avoid shared meals - especially during culturally significant events - may inadvertently exacerbate emotional distress.

While the physiological benefits of PRD are documented, its ethical implementation demands a multidisciplinary approach that includes mental health professionals, family counseling, and community support networks.

Otherwise, we risk trading motor function for emotional ruin.

Susie Deer

January 22, 2026 AT 20:26America is weak

You eat too much protein

Real men eat rice and vegetables

Stop complaining

Just take your pills

And shut up

TooAfraid ToSay

January 23, 2026 AT 02:19Wait so you're saying if I eat protein at night I can still have my jollof rice and fried plantains?

Bro that’s the whole reason I came to America - to eat like this.

So now I gotta choose between walking and eating?

That’s not a diet.

That’s a punishment.

And you wonder why people give up.

They’re not lazy.

They’re just tired of being told their culture is the problem.

Dylan Livingston

January 23, 2026 AT 11:14Oh sweet Jesus. Another ‘miracle diet’ from someone who’s never had to live with this.

You want me to eat oatmeal for breakfast? Like a 1950s housewife?

And save my protein for dinner? So I can sit alone in the dark, chewing a 200-dollar salmon fillet while my husband watches TV?

That’s not a solution.

That’s a performance art piece titled ‘How to Become Invisible’.

And no, I don’t care that it ‘works’.

I don’t want to live like a lab rat.

Let me be broken. At least I’m still human.

Andrew Freeman

January 25, 2026 AT 10:49prd sounds cool but i tried it and my wife made me eat steak at night and now i cant sleep

like literally cant sleep

my legs are jumpy

and my head feels like its buzzing

is that normal

or am i just broken

says haze

January 27, 2026 AT 09:31The irony is not lost on me that we’ve engineered a medication to cross the blood-brain barrier, yet we’re still baffled by amino acid transport kinetics.

It’s a beautiful metaphor for modern medicine: brilliant in theory, clumsy in practice.

Levodopa isn’t the problem - our reductionist view of the body is.

We isolate a molecule, treat it like a bullet, and ignore the entire ecosystem it travels through.

PRD works not because it’s clever - but because it respects complexity.

And yet, we still treat it like a diet hack instead of a systems-level intervention.

How tragic.

How predictable.

Alvin Bregman

January 29, 2026 AT 02:58i read this whole thing and i just wanna say thanks

not because i need to change anything

but because i feel seen

my wife makes me low protein breakfasts and i eat my chicken at 8pm

and yeah sometimes i miss tacos

but i can tie my shoes again

and that’s enough

you dont need to be perfect

you just need to show up

and keep trying

even if its one rice ball at a time

youre not alone