Every time you pick up a prescription for metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin, you’re holding a drug that likely traveled halfway around the world before landing on your pharmacy shelf. These aren’t brand-name pills with flashy marketing-they’re generics, the backbone of affordable healthcare in the U.S. But how do they actually get there? It’s not as simple as a factory → distributor → pharmacy pipeline. The real story is layered with global manufacturing, regulatory hurdles, pricing games, and financial pressures that most patients never see.

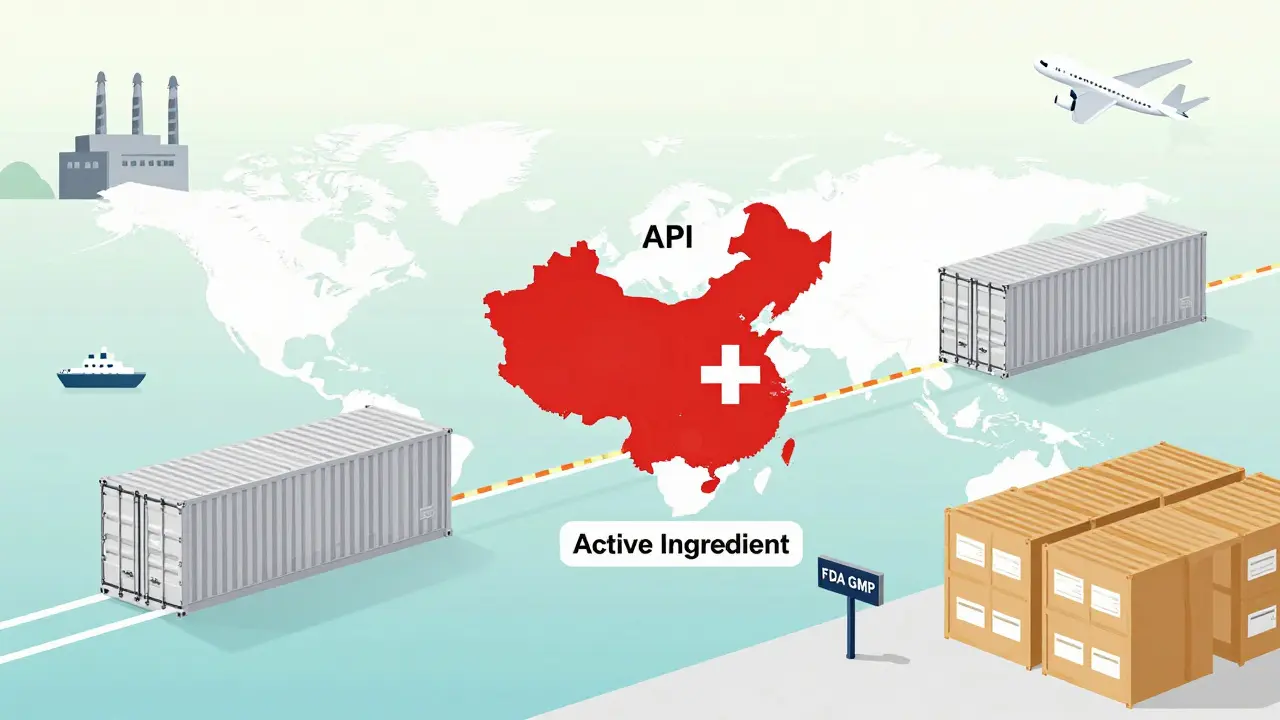

Where It Starts: The Active Ingredient

It all begins with the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient, or API. This is the chemical that actually does the work in your body-like the atorvastatin that lowers cholesterol or the metformin that controls blood sugar. But here’s the twist: 88 percent of all APIs used in U.S. generic drugs are made outside the country. The vast majority come from China and India, where production costs are far lower. The U.S. now produces just 12 percent of its own APIs, down from nearly half just two decades ago. This shift didn’t happen overnight. It was driven by economics. Making APIs requires complex chemistry, strict quality controls, and large-scale facilities. Few U.S. companies could compete on price. So manufacturers outsourced. But that created a vulnerability. When COVID-19 hit, border closures and factory shutdowns in India and China caused shortages of 170 different generic medications. The FDA had to scramble. Inspections of foreign plants jumped from 248 in 2010 to 641 in 2022, but keeping up with thousands of facilities across two continents is a constant challenge.The Approval Hurdle: ANDA and GMP

You can’t just start making a generic drug and sell it. The FDA requires every generic to go through an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This isn’t a full clinical trial like the original brand drug. Instead, the manufacturer must prove their version is bioequivalent-meaning it delivers the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. They don’t need to prove it’s safe again; the brand already did that. But proving bioequivalence is only half the battle. The manufacturing site must follow Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). That means clean rooms, calibrated equipment, batch testing, and documented processes. The FDA can-and does-shut down plants that fail inspections. In 2023, two major Indian API suppliers were blocked from exporting to the U.S. after repeated GMP violations. That’s not a minor hiccup. It can trigger nationwide shortages of common drugs like amoxicillin or hydrochlorothiazide.From Factory to Wholesaler: Bulk and Discounts

Once the drug is made and approved, it’s shipped in bulk to U.S.-based wholesale distributors. These aren’t small mom-and-pop shops. Companies like AmerisourceBergen, McKesson, and Cardinal Health control most of this layer. They buy drugs directly from manufacturers, often at steep discounts tied to how much they order or how fast they pay. This is where the “prompt payment discount” comes in. If a wholesaler pays within 10 days instead of 30, they might get 3-5 percent off the list price. These discounts are negotiated individually. There’s no public pricing table. That lack of transparency is intentional-it keeps competition fierce and margins thin. The price the wholesaler pays is called the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). But here’s the catch: WAC is rarely what pharmacies actually pay. The WAC is more of a starting point for negotiation. Large pharmacy chains like CVS or Walgreens get better deals because they buy in massive volumes. Independent pharmacies? They’re often stuck with higher prices.

The Pharmacy: The Final Stop

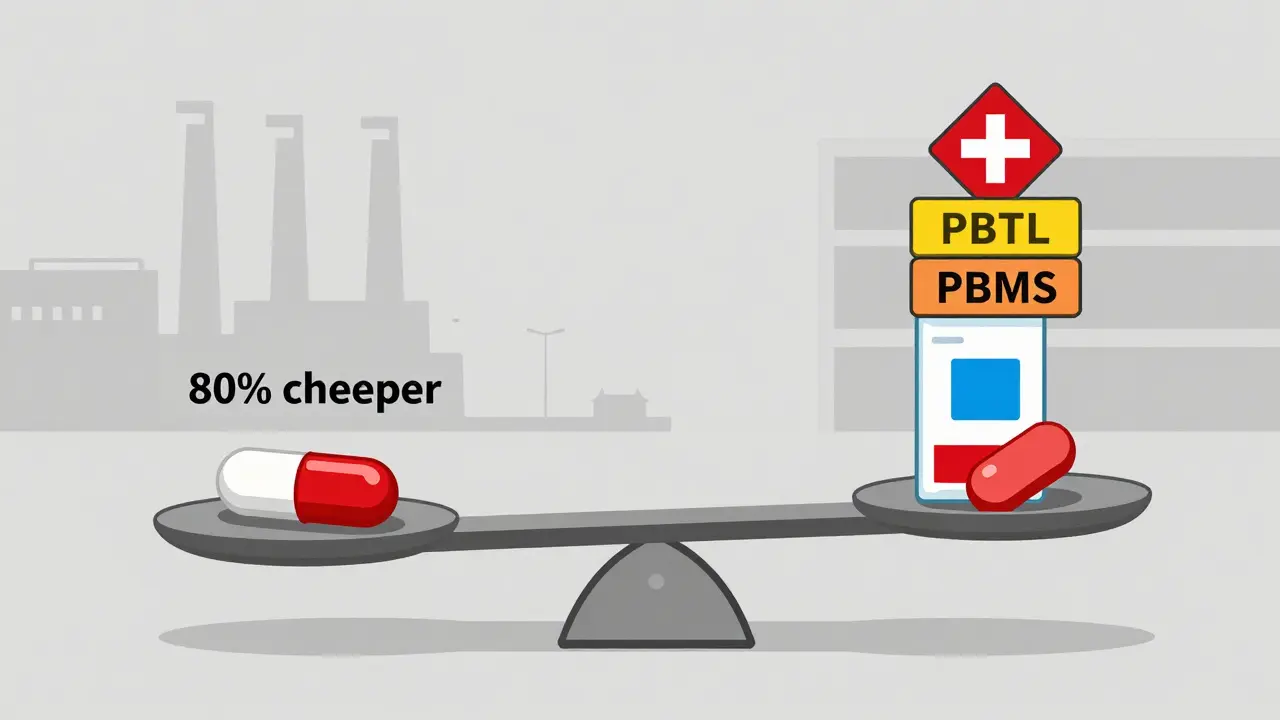

Pharmacies don’t buy directly from manufacturers. They buy from wholesalers. But what they pay isn’t just the wholesale price. They also get reimbursed by insurance-through Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). And this is where things get messy. PBMs handle claims, negotiate rebates, build formularies, and set reimbursement rates. They control about 80 percent of the market, with just three companies-CVS Caremark, OptumRX, and Express Scripts-dominating. For brand-name drugs, PBMs often get rebates from manufacturers. But for generics? Almost never. Instead, PBMs use something called Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). This is a fixed reimbursement rate set for each generic drug-say, $2.50 for a 30-day supply of 10 mg atorvastatin. That rate is based on the lowest acquisition cost among all manufacturers. So if one wholesaler sells it for $1.80, the MAC might be set at $2.00. If your pharmacy paid $2.10 for it, you lose 10 cents per pill. And that’s not rare. A 2023 survey found 68 percent of independent pharmacists say MAC rates are lower than what they paid to buy the drug. That’s why many small pharmacies are struggling. They’re stuck between rising drug costs and falling reimbursement. Some have started buying in cooperatives or joining group purchasing organizations just to get better prices.Who Makes the Money?

Here’s the most surprising part: the company that makes the drug doesn’t get the biggest cut. According to research from the University of Southern California, generic manufacturers capture only 36 percent of the total spending on generic drugs. The rest? Goes to wholesalers, PBMs, pharmacies, and other middlemen. Compare that to brand-name drugs, where manufacturers keep 76 percent of the spending. Why the difference? Because brand companies can charge high list prices and then offer big rebates to PBMs to get on formularies. Generics can’t do that. Their price is already low. There’s no room for rebates. So they compete on volume and cost. This creates a dangerous cycle. As prices drop, manufacturers cut corners. Some shut down. Others merge. The top 10 generic manufacturers now control 65 percent of the U.S. market. That’s less competition. Less innovation. And more risk of shortages if one big player falters.

What’s Changing Now?

The system is under pressure. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 started forcing Medicare to negotiate prices for some drugs. While it doesn’t directly target generics, it’s sending ripples through the system. The FDA’s 2023 Drug Competition Action Plan is trying to speed up approvals and reduce shortages. Some companies are experimenting with AI to predict demand, blockchain to track shipments, and diversifying API sources to avoid over-reliance on one country. But the biggest fix might be policy. Right now, pharmacies are reimbursed based on an outdated formula that doesn’t reflect real-world costs. If MAC rates were tied to actual acquisition costs instead of the lowest possible price, independent pharmacies might survive. If manufacturers weren’t squeezed into near-zero margins, they could invest in better quality control and backup suppliers.Why It Matters to You

You might think, “I just want my pills to be cheap.” And they are-generics cost 80-85 percent less than brand names. But behind that low price is a fragile system. When a factory in India shuts down, or a wholesaler raises prices, or a PBM lowers the MAC rate, you’re the one who feels it. You might wait longer for your refill. Or get a different brand than usual. Or pay more out-of-pocket if your insurance changes its rules. The generic supply chain works because it’s efficient. But efficiency doesn’t mean resilience. It means pushing costs down until someone breaks. Right now, that someone is often the pharmacist on the front line, trying to keep shelves stocked while losing money on every prescription. The truth? You’re not just buying a pill. You’re relying on a global network of factories, regulators, distributors, and negotiators-all working under intense pressure to deliver something simple: a safe, effective, affordable medicine. And that system, for all its flaws, still saves millions of lives every year.Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. They must be bioequivalent-meaning they work the same way in your body. The only differences are in inactive ingredients like color or shape, which don’t affect how the drug works. Millions of people take generics every day without any issues.

Why do generic drugs sometimes look different?

By law, generic drugs can’t look exactly like the brand-name version, even if they contain the same active ingredient. This is to avoid confusion and trademark issues. So the color, shape, or size might be different, but the medicine inside is identical. If you notice a change in appearance, check with your pharmacist-it’s normal and safe.

Why do some pharmacies charge more for the same generic drug?

It’s because of how they buy and get reimbursed. Pharmacies pay different prices to wholesalers based on volume, location, and contracts. Plus, insurance plans reimburse each pharmacy differently using MAC lists. A big chain might get a better deal from a wholesaler and a higher MAC rate from their PBM, while a small pharmacy might pay more and get reimbursed less. Always ask if the pharmacy can match a lower price-many will.

Can a shortage of a generic drug affect my treatment?

Absolutely. When one manufacturer can’t supply enough, shortages can happen quickly because there are often only one or two suppliers for a generic drug. The FDA tracks these shortages, and your pharmacist may need to switch you to another brand or formulation. Don’t stop your medication without talking to your doctor. If you’re on a critical drug like insulin or seizure medicine, ask your pharmacist to monitor for shortages.

Why don’t generic manufacturers offer rebates like brand companies do?

Because their profit margins are already razor-thin. Brand-name companies charge high list prices and then give rebates back to PBMs to get on preferred lists. Generic manufacturers don’t have that luxury-they compete on price, not rebates. Their goal is to sell as much as possible at the lowest possible cost. Offering rebates would mean selling below cost, which isn’t sustainable. That’s why PBMs use MAC pricing instead-it controls costs without needing rebates.

Cheryl Griffith

January 16, 2026 AT 13:31I never realized how fragile this system is. I just take my metformin like it’s cereal-no thought, no worry. But reading this? It’s terrifying. One factory shutdown in India and my life gets disrupted. We treat medicine like a commodity, but it’s literally life support.

And the fact that pharmacists are losing money on every script? That’s not sustainable. They’re the ones holding it all together, and they’re getting crushed.

Ryan Hutchison

January 17, 2026 AT 04:45Of course the U.S. outsources everything. We stopped making anything real decades ago. We want cheap pills but don’t want to pay for the factories that make them. China and India don’t have our labor laws or environmental standards-that’s why they can produce at half the cost. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature of our broken capitalism.

Stop pretending this is about affordability. It’s about profit. And we’re paying the price in shortages and scared pharmacists.

Corey Sawchuk

January 17, 2026 AT 13:17Nicholas Gabriel

January 19, 2026 AT 06:54Let’s be real: this isn’t just about supply chains-it’s about power. PBMs control everything. They set MAC rates, they dictate which drugs get covered, they negotiate behind closed doors, and they pocket the difference. And who suffers? The independent pharmacist. The diabetic on a fixed income. The elderly who can’t afford to switch brands.

We need transparency. We need to ban MAC rates that are below cost. We need to force PBMs to disclose their rebates-even for generics. And we need to incentivize domestic API production-not just for national security, but for ethical manufacturing.

This isn’t radical. It’s basic fairness. We don’t let companies sell food at a loss and then blame the grocer when people starve. Why do we do it with medicine?

And yes, I know some will say ‘it’s too complicated.’ But if we can regulate Wall Street, we can regulate pharmaceutical middlemen. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way.

evelyn wellding

January 20, 2026 AT 09:37OMG this is so eye-opening!! 🥺 I had no idea my $4 generic was actually costing my pharmacist money 😭 We need to support local pharmacies-they’re heroes!!

Also, if you ever get a different-looking pill? Don’t panic! It’s probably just another manufacturer. Ask your pharmacist-they’ll tell you it’s the same stuff. 💊❤️

john Mccoskey

January 21, 2026 AT 06:21Let’s cut through the sentimental nonsense. The system works exactly as intended: maximize profit, minimize responsibility. The FDA doesn’t have the manpower to inspect every plant. The wholesalers exploit volume discounts to squeeze margins. PBMs are rent-seekers who extract value without creating it. Generic manufacturers are price-takers in a race to the bottom.

There is no moral failing here-only economic logic. The U.S. consumer wants cheap drugs. The market delivers. The collateral damage-pharmacists, patients, supply chain resilience-is irrelevant to the calculus of shareholder value.

Calling for ‘fairness’ or ‘supporting small pharmacies’ is nostalgia for a pre-capitalist fantasy. The solution isn’t regulation-it’s acceptance. We are a nation that outsources everything from socks to semiconductors. Why should medicine be sacred?

If you want resilience, pay more. If you want cheap, accept the fragility. There are no free lunches. Only invisible hand-shaped knives.

Melodie Lesesne

January 21, 2026 AT 19:04Love how you laid this out-it’s wild to think about how many people are involved just to get one pill to your hand.

My cousin works at a small pharmacy in Nova Scotia, and she told me they just started buying generics in bulk with a co-op of other local shops. It’s helping them stay afloat. Maybe that’s the real innovation-not tech or blockchain, but community.

Corey Chrisinger

January 23, 2026 AT 15:25There’s a quiet tragedy here: we’ve turned medicine into a commodity, but we still treat it like a miracle.

We don’t question the origin of our coffee, our phones, our sneakers-but when a pill changes shape, we panic. We demand safety, yet we refuse to pay for it. We want the convenience of a 24-hour pharmacy, but we balk at the idea of paying $1 more for a drug made in Ohio instead of Hyderabad.

Maybe the real question isn’t ‘how do pills get here?’

It’s ‘why do we expect miracles without paying for the machinery that makes them possible?’

Bianca Leonhardt

January 23, 2026 AT 20:54People whining about small pharmacies? Get over it. If you can’t compete with volume pricing, you shouldn’t be in business. This isn’t a charity. It’s capitalism. And if you’re losing money on generics, you’re doing it wrong.

Also, stop acting like China and India are villains. They’re just better at this than we are. We outsourced because we were lazy. Now we’re mad the system works? Grow up.