A moving clot can shut down an organ in minutes. That’s the hard truth about embolism. If you learn to spot it quickly and know what treatments exist, you can change the story-yours or someone else’s. This guide is straight to the point: what an embolism is, how to recognize it, what doctors do, and what you can do to prevent it. No fluff, just what helps you act.

TL;DR: Key takeaways you can use right now

- Embolism means something (usually a blood clot) travels through your bloodstream and blocks an artery. Where it lands determines the symptoms and urgency.

- Red flags: sudden shortness of breath or chest pain (pulmonary), one-sided weakness or confusion (stroke), cold painful limb (arterial limb), severe belly pain out of proportion (mesenteric).

- Don’t wait with stroke or suspected pulmonary embolism-call emergency services immediately (000 in Australia, 911 US/Canada, 112 EU, 999 UK).

- Treatment depends on type and severity: anticoagulants (blood thinners), thrombolysis (clot-busting), thrombectomy (mechanical removal), or supportive care.

- Prevention is practical: move often, manage estrogen use, treat underlying conditions, get proper clot-prevention after surgery, and discuss long-term therapy if clots were unprovoked.

What an embolism is, why it happens, and the main types

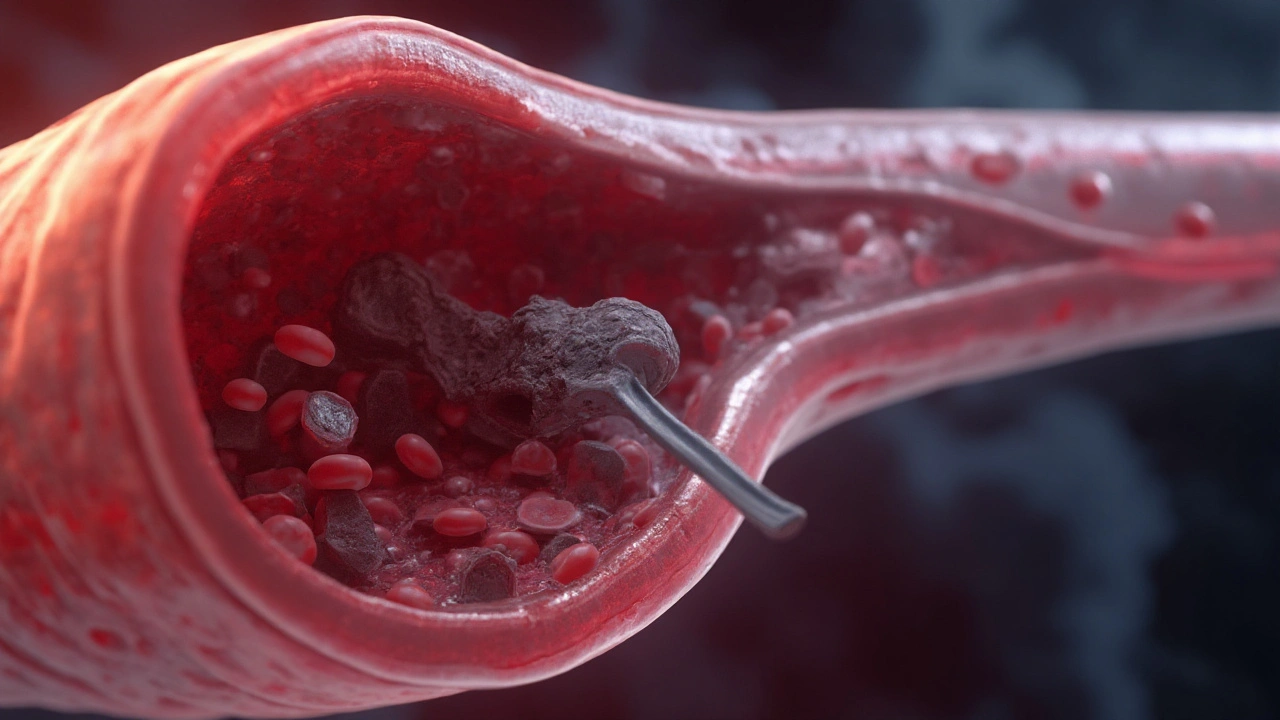

An embolism is a traveling blockage. Most of the time it’s a blood clot that forms in one spot (often the deep veins of the leg), breaks off, and rides the circulation until it wedges into a smaller artery. Less often, the plug can be air, fat, amniotic fluid, bacteria-laden debris, or even a tumor fragment.

Why clots form in the first place often comes down to a simple triad: sluggish blood flow, a sticky/clot-prone state, and damage to the vessel wall. You’ll hear clinicians call this Virchow’s triad. In real life, that looks like: a long-haul flight or bed rest (sluggish flow), pregnancy, cancer, infection, or certain medications like estrogen (stickier blood), and recent surgery or trauma (vessel damage).

Common types you’ll actually hear about:

- Thromboembolism (blood clot): the big one. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that breaks off and causes pulmonary embolism (PE). A clot in the heart (from atrial fibrillation or a damaged valve) that shoots to the brain and causes an ischemic stroke.

- Air embolism: air enters a vein or artery via a line mishap, injury, or diving incident.

- Fat embolism: marrow fat enters blood after major bone fractures or orthopedic surgery.

- Amniotic fluid embolism: rare, dangerous complication around delivery.

- Septic emboli: infected clumps from endocarditis that can seed the brain, lungs, or elsewhere.

How common is this? Venous thromboembolism (DVT/PE together) affects roughly 1-2 people per 1,000 each year in developed countries. Pulmonary embolism alone accounts for tens of thousands of hospitalizations annually. Without treatment, large PE can kill up to 1 in 3. With modern therapy, early mortality drops to the low single digits. These numbers are drawn from large registry studies and national surveillance reports (think national health agencies and cardiology societies).

Who’s at higher risk?

- Recent surgery or hospital stay, especially orthopedics or cancer surgery

- Immobilization: long flights or drives, illness in bed, casted limb

- Estrogen exposure: combined oral contraceptives, hormone therapy

- Pregnancy and the 6 weeks after delivery

- Cancer and some chemotherapy agents

- Prior VTE, family history, or inherited thrombophilia (e.g., Factor V Leiden)

- Major trauma, central venous lines, and some infections

- Obesity, smoking, inflammatory diseases, and increasing age

Note for travelers: long-haul flights (like Sydney to London) raise VTE risk about 2-4 times, but the absolute risk for a healthy person is still low. If you stack risks-say, prior DVT plus estrogen therapy-that’s different. Plan prevention.

Symptoms you must not ignore-and how to act fast

Symptoms depend on where the embolus lands. The patterns below are worth memorising. They save lives.

Pulmonary embolism (clot to the lungs):

- Sudden unexplained shortness of breath, worse with activity

- Pleuritic chest pain (sharp, worse with deep breath)

- Fast heart rate, light-headedness, fainting; sometimes cough or blood-streaked sputum

- Clue from the legs: calf pain or swelling (a DVT source)

Stroke (clot to the brain):

- FAST test: Face droop, Arm weakness, Speech trouble, Time to call emergency

- Other signs: sudden vision loss, severe imbalance, sudden severe headache

Coronary embolism (clot to a heart artery):

- Chest pressure or tightness, often with sweat, nausea, or breathlessness

Acute limb ischemia (clot to an arm or leg artery):

- Sudden pain, pale or blue skin, cold limb, weak or absent pulse, numbness

Mesenteric ischemia (clot to gut blood supply):

- Severe abdominal pain that feels “out of proportion” to exam findings, nausea/vomiting

What to do if you suspect PE or stroke:

- Call emergency services immediately (000 AU, 911 US/Canada, 112 EU, 999 UK). Do not drive yourself.

- Keep still. For suspected DVT/PE, walking can dislodge more clot.

- Avoid food or drink in case urgent procedures are needed.

- Note the time symptoms started. For stroke, treatment windows are time-critical.

Don’t self-diagnose with a smartwatch or wait for a GP slot when you have red flags. Minutes matter for stroke and massive PE.

Common pitfalls to avoid:

- Assuming chest pain is “just anxiety” or “a pulled muscle” after a flight

- Masking pain with ibuprofen while on blood thinners (raises bleeding risk)

- Stopping anticoagulants early because you “feel fine”

- Skipping imaging for a swollen leg when you’ve recently had surgery or immobilisation

Diagnosis and treatment options that actually change outcomes

Clinicians use a stepwise approach: estimate risk, confirm with tests, then treat according to severity.

How doctors diagnose:

- Risk scores: Wells, Geneva, and PERC help decide who needs testing.

- Blood tests: D-dimer is very sensitive. In low-risk patients, a normal result can safely rule out VTE. Age-adjusted cutoffs improve accuracy in older adults.

- Imaging: Doppler ultrasound (DVT), CT pulmonary angiography (PE), V/Q scan when CT isn’t suitable, and CT/MR angiography for stroke. ECG, troponin, and BNP can help risk-stratify PE.

Treatment, simplified:

- Anticoagulation (first-line for most clot-related emboli): direct oral anticoagulants (apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, edoxaban), low-molecular-weight heparin, or warfarin in specific cases. Duration depends on cause: often 3 months if provoked by a transient risk (like surgery), longer if unprovoked or ongoing risk (like active cancer).

- Thrombolysis (clot-busting drug like alteplase): reserved for high-risk PE with shock, and for eligible ischemic strokes within defined time windows after onset.

- Mechanical thrombectomy: catheter-based clot removal for massive/submassive PE in selected centres; standard of care for large-vessel occlusion strokes when within window.

- IVC filter: considered if you have a DVT/PE but absolutely cannot receive anticoagulation. Should be retrieved as soon as possible once blood thinners resume.

- Supportive care: oxygen, fluids, blood pressure support; pain control that doesn’t increase bleeding risk.

Special situations:

- Pregnancy: LMWH is preferred. DOACs are generally avoided. Postpartum risk peaks in the first 6 weeks.

- Cancer-associated thrombosis: LMWH or selected DOACs; choice depends on cancer type and bleeding risk (e.g., GI cancers need caution).

- Air embolism: 100% oxygen, left lateral positioning, and sometimes hyperbaric therapy. Prevention during line placement is key.

- Fat embolism: supportive care (oxygen, ventilation if needed). Prevention is early fracture stabilisation.

- Amniotic fluid embolism: rapid resuscitation, blood product support; it’s rare but high-acuity.

What the evidence and guidelines say (summarised in plain language):

- Modern guidelines from chest physicians and cardiology societies (e.g., CHEST 2021 VTE, ESC 2019/2020 PE updates, AHA/ASA stroke guidance) prioritise DOACs for most VTE because they’re effective, simpler, and cause less major bleeding than warfarin in many patients.

- Minimum treatment for a provoked DVT/PE is typically 3 months. Unprovoked events may need extended therapy; low-dose DOAC regimens can maintain protection with lower bleeding risk.

- For stroke, imaging decides who gets thrombolysis or thrombectomy; speed to treatment strongly predicts recovery.

Key numbers worth knowing:

| Metric | Typical figure | Context |

|---|---|---|

| VTE incidence | 1-2 per 1,000 per year | Higher with age, hospitalisation, cancer |

| PE mortality untreated | Up to ~30% | Large registry/observational data |

| PE mortality with treatment | ~2-8% | Depends on severity and comorbidities |

| Recurrence after unprovoked VTE (off therapy) | ~10% in year 1; ~5%/yr thereafter | Risk accumulates over time |

| D-dimer sensitivity | >95% in low-risk patients | High negative predictive value |

| DOAC vs warfarin major bleeding | ~30-40% relative reduction | Meta-analyses of VTE treatment |

Practical decision help (talk this through with your clinician):

- If your clot followed a major, temporary trigger (e.g., knee replacement), three months is often enough.

- If unprovoked, or you have ongoing risks (e.g., cancer, recurrent events), extended anticoagulation is often advised; low-dose DOAC maintenance is a common strategy.

- If bleeding risk is high, discuss alternatives like shorter therapy, close follow-up, and non-drug prevention measures.

Medicines and everyday life tips:

- DOACs: take consistently; missing doses reduces protection fast. Watch for bleeding: black stools, prolonged nosebleeds, unexpected bruising.

- Warfarin: keep vitamin K intake steady (greens are fine; just be consistent). Check INR as scheduled. Many drugs interact-always ask before new meds.

- Pain relief: paracetamol/acetaminophen is usually safer than NSAIDs while on anticoagulants, unless your doctor says otherwise.

Prevention, recovery, and the questions people actually ask

Simple prevention you can start today:

- Move every hour on long trips; do ankle circles and calf pumps in your seat. Choose an aisle if you can.

- Hydrate; go easy on alcohol and sedatives when you’re immobile.

- After surgery or hospitalisation: ask, “What’s my clot prevention plan?” This could be early walking, compression, and short-term blood thinners.

- Discuss estrogen-containing contraception if you have VTE risks or a prior clot; many safer alternatives exist.

- Manage the big ones: stop smoking, treat sleep apnoea, maintain healthy weight, and control inflammatory conditions.

Travel-specific tips (pragmatic, not paranoid):

- Low risk, healthy travelers: movement and hydration are enough.

- Higher risk (recent surgery, prior VTE, active cancer, pregnancy): add below-knee compression stockings (properly fitted). Some may warrant a single preventive dose of LMWH-decide with your clinician before you fly.

Recovery after PE or DVT-what to expect:

- Fatigue and breathlessness can linger for weeks. Gentle walking is good; increase gradually. Cardio rehab or supervised exercise helps some people.

- Post-PE syndrome (ongoing breathlessness) is real. If you feel stuck at 3 months, ask about re-evaluation for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

- Compression stockings can help with leg symptoms after DVT; for preventing post-thrombotic syndrome, evidence is mixed-use if they make your leg feel better.

- Return to flying: once you’re stable on anticoagulation, many clinicians are comfortable with flights after 2 weeks; longer if your PE was severe. Get personalised clearance.

Mini-FAQ

- How long will I be on blood thinners? For a surgery-provoked DVT/PE, often 3 months. For unprovoked or recurrent events, many stay on longer at a reduced dose. Your bleeding risk and preferences matter.

- Can I exercise? Yes-start low, go slow. Walking and cycling are great. High-impact or contact sports are risky while on anticoagulants due to bleeding.

- Do I need genetic testing? Not routinely. It’s considered in young patients with unprovoked clots or strong family history, especially if results would change long-term management.

- Are compression stockings useful? For travel and symptomatic leg swelling, yes. For preventing long-term post-thrombotic syndrome, evidence is mixed-use based on comfort and clinician advice.

- What about aspirin? If you stop anticoagulation after an unprovoked clot, low-dose aspirin gives modest extra protection, but it’s weaker than a DOAC. Discuss the trade-offs.

- Do vaccines or flights cause clots? Routine vaccines don’t increase VTE risk in the general population. Flights raise risk slightly via immobility; move, hydrate, and add measures if you’re high-risk.

- Can I drink alcohol on blood thinners? Small amounts, spaced out, are usually fine; heavy drinking increases bleeding risk and can mess with warfarin control.

- IVC filter-do I need it removed? Yes, if it was placed temporarily. Retrieval reduces long-term complications. Ask about a retrieval date.

- Does COVID-19 change things? Severe infection increases clot risk. Standard prevention in hospital plus early movement after recovery still applies.

Checklists you can print or save

Suspected PE or stroke-quick action list:

- Call emergency (000 AU, 911 US/Canada, 112 EU, 999 UK).

- Note the exact time symptoms began.

- Keep the person still and comfortable; no food/drink.

- List medications, especially blood thinners and recent surgeries.

- If trained and needed, start basic life support.

Post-DVT/PE daily routine:

- Take anticoagulant on schedule; set reminders.

- Scan for bleeding signs; report anything unusual.

- Walk daily; track distance or minutes.

- Plan follow-up: imaging or clinic review at 3 months to reassess duration.

- Ask about a medical alert card noting your anticoagulant.

Next steps and troubleshooting by scenario

- If you have symptoms now: get urgent medical help. Don’t self-transport with severe chest pain, breathlessness, or stroke signs.

- If you were just diagnosed: ask, “What caused this? How long will treatment last? What’s my bleeding risk?” Clarify dose changes (many DOACs have a higher starting dose for 1-3 weeks).

- If you keep getting clots: check adherence, re-evaluate for hidden risks (e.g., cancer screening guided by age and symptoms), and consider switching anticoagulants or adding specialist input.

- If you can’t tolerate a DOAC: LMWH or warfarin remain options. Don’t quit therapy without an agreed plan.

- If you’re planning surgery or dental work: you may need to pause anticoagulation. Get a written peri-procedural plan from your clinician.

- If you’re pregnant or planning pregnancy: see a specialist early; LMWH plans are tailored and safe in pregnancy.

- If severe leg pain/swelling worsens suddenly: urgent reassessment-rarely, a large iliofemoral DVT needs intervention to save the limb.

Credible sources clinicians rely on for this topic include guideline bodies and large registries, such as CHEST antithrombotic therapy guidelines for VTE (latest updates in the early 2020s), European Society of Cardiology guidance on pulmonary embolism, American Heart Association/American Stroke Association stroke pathways, and national health agencies (e.g., Australia’s national institutes). These shape the risk scores, imaging choices, and treatment durations you’ll encounter in clinic.

You don’t need to memorise every detail. Remember the patterns, move early on prevention, and act fast when red flags appear. That’s the part that saves lives.

Ted Mann

August 30, 2025 AT 00:15Reading about embolisms makes me think of life’s sudden roadblocks – you never see them coming until they slam into place. The guide nails down the basics without drowning you in jargon, which is a rare treat. Knowing the red‑flag symptoms can be the difference between a quick rescue and a nightmare. I especially like the tip to move every hour on long trips; it’s simple and powerful. Keep sharing clear medical breakdowns like this, they’re more valuable than a thousand opinion pieces.

Brennan Loveless

September 3, 2025 AT 20:15All this hype about clot prevention is just fear‑mongering, the body can handle it.

Vani Prasanth

September 8, 2025 AT 16:15Thank you for putting together such a clear, step‑by‑step explanation. As someone who has helped a family member through a DVT, I can attest to the value of the quick‑action checklist. The prevention tips, especially the travel advice, are spot‑on and easy to follow. Keep the community informed – knowledge truly saves lives.

Maggie Hewitt

September 13, 2025 AT 12:15Oh great, another 5‑minute read on why clots are the ultimate party crashers.

Mike Brindisi

September 18, 2025 AT 08:15Embolism is a blockage that travels through the bloodstream and can stop blood flow to vital organs. The most common source is a deep vein thrombosis in the legs. Virchow’s triad explains why clots form it’s all about stasis hypercoagulability and endothelial injury. Pulmonary embolism presents with sudden shortness of breath chest pain and rapid heart rate. Stroke symptoms follow the FAST mnemonic and need immediate medical attention. Anticoagulants like apixaban rivaroxaban and dabigatran have become first‑line therapy. Knowing the risk factors such as recent surgery long‑haul travel and hormone therapy helps prevent these events.

Steven Waller

September 23, 2025 AT 04:15When we consider the circulatory system as a network of highways, an embolus is the unexpected roadblock that forces us to reevaluate our journey. Understanding the mechanisms behind clot formation empowers us to take proactive steps, rather than reacting in panic. The guide’s emphasis on rapid response mirrors the philosophical principle that awareness precedes action. By sharing these insights, we collectively build a safety net for those who might otherwise be caught off‑guard. Let’s continue to blend medical knowledge with compassionate guidance.

Puspendra Dubey

September 28, 2025 AT 00:15Yo bro what a ride🚀 the blood clot saga is like drama in my life lol

When you sit cramped on a flight you feel the panic rising but remember the simple moves – stand up walk around and stay hydrated 🙏🏽

Shaquel Jackson

October 2, 2025 AT 20:15Honestly this whole “move every hour” tip feels like a lazy excuse for people who can’t be bothered to actually get medical help 😒

Tom Bon

October 7, 2025 AT 16:15I appreciate the concise presentation of risk factors and treatment pathways; the structured format facilitates quick reference for both clinicians and laypersons alike.

Clara Walker

October 12, 2025 AT 12:15What they don’t tell you is that the pharmaceutical industry has a vested interest in keeping the public scared of “clots” so they can push endless prescriptions and profit from the fear‑based market. Every new “guide” is just a thinly veiled advertisement for the next blockbuster anticoagulant, and the real solution – lifestyle changes – get buried under a mountain of patent jargon. Stay vigilant, question the motives, and don’t let corporate hype dictate your health decisions.

Jana Winter

October 17, 2025 AT 08:15While the article is generally thorough, there are a few grammatical oversights that merit correction: “blood clot” should be hyphenated when used as an adjective (e.g., “blood-clot formation”) and “risk‑factors” does not require a hyphen when used as a noun. Additionally, the phrase “high‑risk PE” is missing a hyphen. Maintaining precision in language mirrors the precision required in medical practice.

Linda Lavender

October 22, 2025 AT 04:15Embarking upon the subject of embolism is akin to opening a grand, labyrinthine tome of vascular intrigue, wherein each chapter unfurls a cascade of physiological marvels and perils that bespeak humanity’s perpetual dance with mortality. The notion that a solitary clot, forged in the quiet shadows of a dormant vein, can embark upon a transcontinental voyage within our own circulatory highways evokes both awe and dread, for it underscores the fragile equilibrium that sustains life itself. One must first acknowledge the triad of Virchow – stasis, hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury – as the triumvirate that summons the clot’s genesis, a concept that, though seemingly rudimentary, forms the cornerstone of preventative strategy. When such a rogue element reaches the pulmonary artery, the resulting pulmonary embolism manifests with an abrupt gasp of breath, an austere chest pain, and a heart that hurries as though fleeing an unseen specter. Conversely, should the clot breach the cerebral barricades, the brain’s eloquent symphony is shattered, yielding the classic FAST tableau of facial droop, arm weakness, and slurred speech – a tableau that demands immediate, decisive intervention. The therapeutic armamentarium, from low‑molecular‑weight heparin to the sleek, oral direct factor Xa inhibitors, reflects the medical community’s relentless pursuit of efficacy tempered by safety, each agent offering its own nuanced profile of advantages and caveats. Beyond pharmacologic measures, the interventionalist’s scalpel – be it in the form of catheter‑directed thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy – represents a bold frontier wherein technology wrests clots from the perilous throes of occlusion. Yet, none of these advancements can eclipse the primal wisdom that movement, hydration, and vigilant awareness constitute the most elemental bulwarks against thrombotic tyranny. The modern traveler, ensconced within pressurized cabins, must therefore eschew complacency, opting instead for periodic ambulation, ankle flexion, and perhaps graduated compression stockings, lest the silent specter of deep‑vein thrombosis lurk in the stillness of seated repose. Moreover, the nuanced interplay of hormonal modulation, particularly through exogenous estrogen, adds another layer of complexity, demanding that clinicians tailor prophylaxis with an eye toward individualized risk stratification. In the realm of obstetrics, the peril intensifies, for the postpartum period births a hypercoagulable state that can culminate in catastrophic amniotic fluid embolism, a calamity for which preparedness and rapid resuscitation remain paramount. As we navigate this intricate tapestry, the importance of patient education cannot be overstated; the ability to discern red‑flag symptoms, to summon emergency services without hesitation, and to adhere faithfully to anticoagulant regimens underpins the very essence of survivability. Finally, it is incumbent upon the medical establishment to disseminate this knowledge with clarity, brevity, and compassion, ensuring that the layperson is not lost amid an ocean of jargon but instead is equipped with actionable insight. In sum, the saga of embolism is a testament to the delicate balance of human physiology, the relentless ingenuity of medical innovation, and the unwavering responsibility of each individual to remain vigilant, informed, and proactive in the face of vascular adversity.

Jay Ram

October 26, 2025 AT 23:15Your deep dive is impressive – thanks for the thorough perspective! It reminds us that knowledge truly is power, and staying proactive can save lives. Keep the detailed explorations coming.

Elizabeth Nicole

October 31, 2025 AT 19:15Seeing all the practical steps laid out makes me feel more confident that I can watch out for warning signs and act fast if needed. The travel tips are especially handy for my upcoming trip, and the recovery advice feels realistic and supportive. It’s reassuring to know that with the right vigilance and medical help, most people bounce back well.

Dany Devos

November 5, 2025 AT 15:15The article presents an exhaustive overview of embolic pathology, yet it could benefit from a more structured hierarchy of decision‑making algorithms to aid clinicians in rapid triage. Incorporating flowcharts would enhance usability without compromising the depth of information.

Sam Matache

November 10, 2025 AT 11:15Another bland medical rundown? Seriously, it’s like watching paint dry while the author pretends we haven’t seen the same bullet points a hundred times. If they wanted to spark interest they’d need more drama than a sterile checklist.

Hardy D6000

November 15, 2025 AT 07:15While the critique highlights a valid point regarding engagement, the factual accuracy and comprehensiveness of the guide remain unchallenged; the inclusion of evidence‑based guidelines underpins its clinical relevance.

Amelia Liani

November 20, 2025 AT 03:15Reading through these insights fills me with a profound respect for the delicate balance our bodies maintain. Thank you all for sharing expertise and compassion – together we can empower others to recognize and confront embolic threats.