Cephalosporin Cross-Reactivity Risk Calculator

This tool estimates the actual risk of allergic reaction when using cephalosporins in patients with penicillin allergy history. Based on current medical evidence, not the outdated 10% rule.

Results based on CDC and IDSA guidelines. Not a substitute for clinical judgment or allergy testing.

For decades, doctors were told to avoid cephalosporins in patients with penicillin allergies. The rule was simple: 10% cross-reactivity. If you were allergic to penicillin, you had a 1 in 10 chance of reacting to any cephalosporin. That number showed up on drug labels, in hospital protocols, and in medical school textbooks. But here’s the truth: that number is wrong. And it’s costing patients - and the healthcare system - more than we realize.

Why the 10% Rule Is Outdated

The 10% cross-reactivity figure came from studies in the 1960s and 70s. Back then, cephalosporin production wasn’t clean. The mold used to make these drugs, Cephalosporium, often carried traces of penicillin. So when patients reacted to cephalosporins, it wasn’t because the cephalosporin itself triggered the allergy - it was because of leftover penicillin contamination. Modern manufacturing has eliminated this issue. Today’s cephalosporins are pure. Yet, the old warning stuck.Recent studies tell a different story. A review of 12 studies from the 1980s onward, involving over 400 patients with confirmed penicillin allergies, found the real cross-reactivity rate is closer to 2% to 5%. For third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins like ceftriaxone and cefepime, the rate drops below 1%. That’s not a small difference - it’s a game-changer.

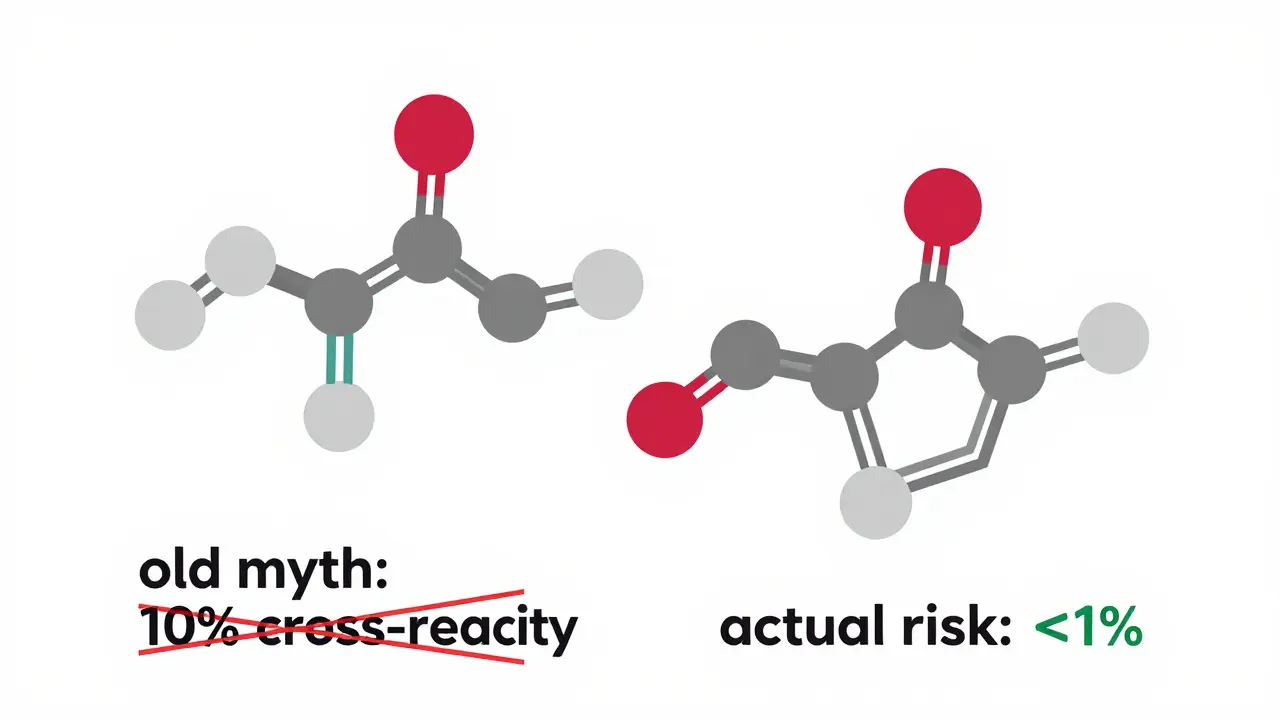

It’s Not the Ring - It’s the Side Chain

Penicillins and cephalosporins both have a beta-lactam ring. That’s the part everyone used to blame. But research now shows the real culprit isn’t the ring. It’s the side chain - the chemical group sticking off the main structure.Think of it like this: two cars might have the same engine (the beta-lactam ring), but if they have different bumpers, paint jobs, and wheels (the side chains), they’re not the same to your immune system. Your body doesn’t react to the engine - it reacts to the bumper.

Studies show that 42% to 92% of penicillin allergic reactions are triggered by side-chain structures, not the core ring. That’s why amoxicillin and ampicillin - which have nearly identical side chains - cross-react with each other. But ceftriaxone, with its very different side chain, barely triggers any reaction in penicillin-allergic patients.

Generations Matter - A Lot

Cephalosporins are grouped into five generations based on their antimicrobial range and side-chain structure. But here’s what really matters for allergies:- First-generation (cefazolin, cephalexin): Closest to penicillin in side-chain structure. Cross-reactivity risk: 1%-8%. Avoid if you have a history of IgE-mediated reactions (hives, swelling, anaphylaxis).

- Second-generation (cefuroxime, cefoxitin): Slightly less similar. Risk: still in the 1%-8% range, but variable.

- Third-generation (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefixime): Very different side chains. Cross-reactivity: less than 1%. Safe for most penicillin-allergic patients - even those with past hives or anaphylaxis - if it’s been more than 10 years since the reaction.

- Fourth-generation (cefepime): Even more distinct. Risk: negligible.

- Newer agents (ceftolozane/tazobactam): Not classified in a generation. No data yet, but side-chain structure suggests low risk.

Here’s the kicker: if you had a rash from penicillin 20 years ago - not hives, not trouble breathing - you’re likely not truly allergic at all. Studies show 90-95% of people who say they’re allergic to penicillin turn out to be fine after proper testing.

What Does “Allergic” Even Mean?

Not all reactions are true allergies. Many people confuse side effects with allergies. A stomachache? Not an allergy. A mild rash that showed up days later? Often not IgE-mediated. True allergic reactions - the kind that cause anaphylaxis - involve the immune system releasing histamine within minutes to hours. Symptoms include hives, swelling of the lips or throat, wheezing, or a sudden drop in blood pressure.One study at Kaiser Permanente followed 3,313 patients who claimed they were allergic to cephalosporins. They were given cephalosporins anyway - mostly first-gen - and not one had anaphylaxis. That’s not a fluke. It means most of those “allergies” were never real.

Even people without any penicillin history can react to cephalosporins. About 1% to 3% of all patients develop immune-mediated reactions to cephalosporins, regardless of penicillin history. That’s why you can’t assume safety just because someone isn’t penicillin-allergic. But that’s also why you shouldn’t assume danger just because someone says they are.

What Should Doctors Do?

The CDC, Medsafe, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America all agree: stop using the 10% rule. Here’s what they recommend:- If a patient has a history of anaphylaxis, hives, or angioedema to penicillin within the last 10 years: avoid first- and second-generation cephalosporins. Third- and fourth-generation are generally safe.

- If the reaction was a delayed rash (no breathing issues, no swelling): cephalosporins can usually be given with monitoring - no skin test needed.

- If the patient has no history of IgE-mediated reactions: third-generation cephalosporins like ceftriaxone are safe to use, even for life-threatening infections like meningitis or gonorrhea.

- For patients with unclear histories: refer for penicillin skin testing. A negative test means 90-95% of patients can safely take penicillin - and by extension, most cephalosporins.

And here’s the best part: when you stop avoiding cephalosporins unnecessarily, you avoid worse drugs. Instead of using vancomycin, clindamycin, or fluoroquinolones - which are broader-spectrum and more likely to cause C. diff infections or antibiotic resistance - you can use a targeted, safer option.

Why This Still Matters

About 10% of Americans say they’re allergic to penicillin. That’s over 30 million people. But only about 1% of them are truly allergic. The rest are either misdiagnosed, outgrew the allergy, or had a side effect mistaken for an allergy.Because of outdated beliefs, those 30 million people are often given antibiotics that are less effective, more expensive, and more dangerous. The CDC estimates this mismanagement adds billions of dollars to healthcare costs each year. It also increases the risk of drug-resistant infections and hospital-acquired C. diff.

Some hospitals have started “penicillin allergy delabeling” programs. They test patients, update records, and switch them to better antibiotics. The results? Broad-spectrum antibiotic use drops by 10-25%. Hospital stays get shorter. Infections get easier to treat.

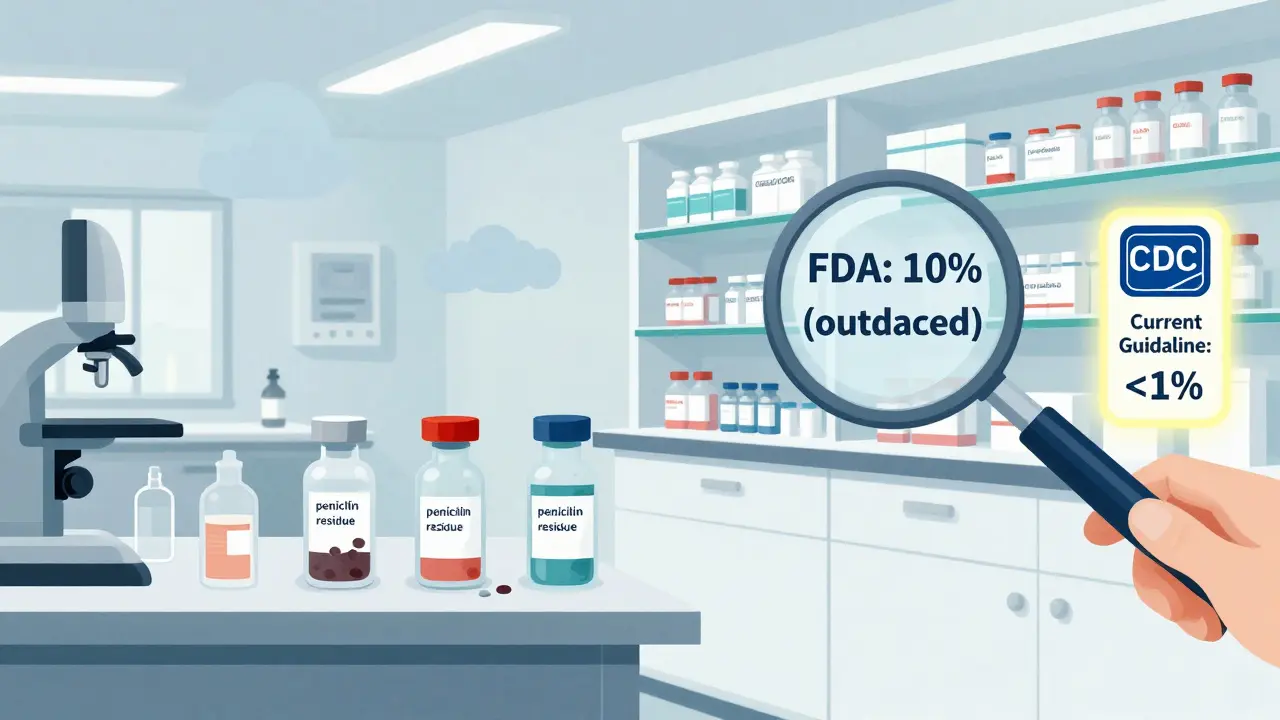

The FDA’s Problem

Here’s the frustrating part: the FDA still lists a 10% cross-reactivity warning on most cephalosporin labels. Why? Because they haven’t updated their labeling to reflect current science. Meanwhile, the CDC, Medsafe, and major medical societies have moved on.This creates confusion. A doctor in a small clinic might see the FDA warning and play it safe - even if the evidence says otherwise. A pharmacist might refuse to fill the script. A patient might be denied the best treatment because of a label written decades ago.

It’s not about ignoring risk. It’s about understanding it correctly. The risk isn’t 10%. It’s not even 5%. For most patients, it’s less than 1% - and that’s worth the benefit of using the right antibiotic.

What Patients Should Know

If you’ve been told you’re allergic to penicillin:- Ask: “What exactly happened? Was it hives? Swelling? Trouble breathing?”

- If it was just a rash or upset stomach, you might not be allergic at all.

- Ask your doctor if you can be tested. Skin testing is safe, quick, and accurate.

- If you need an antibiotic for an infection - especially something serious - don’t automatically refuse cephalosporins. Ask if a third-generation one like ceftriaxone is an option.

- Update your medical records. If you’ve been tested and cleared, make sure your doctor knows.

Antibiotics are powerful tools. But they’re only as good as the decisions behind them. When we cling to old myths, we hurt patients - not protect them.

Is it safe to take ceftriaxone if I’m allergic to penicillin?

Yes, for most people. Third-generation cephalosporins like ceftriaxone have a cross-reactivity rate of less than 1% with penicillin-allergic patients, especially if the penicillin reaction wasn’t anaphylaxis or hives. The CDC and major medical societies consider it safe for patients without recent IgE-mediated reactions.

What’s the difference between a penicillin allergy and a side effect?

A true penicillin allergy involves the immune system and causes symptoms like hives, swelling of the face or throat, wheezing, or anaphylaxis - usually within minutes to hours. Side effects like nausea, diarrhea, or a mild rash that appears days later are not true allergies. Many people mistake side effects for allergies, which is why up to 95% of people labeled penicillin-allergic are not actually allergic.

Can I outgrow a penicillin allergy?

Yes. Studies show that about 80% of people who had a penicillin allergy as children lose it within 10 years. Even if you had a reaction decades ago, you may no longer be allergic. Skin testing can confirm whether the allergy still exists.

Why do some doctors still avoid cephalosporins for penicillin-allergic patients?

Many doctors still rely on outdated guidelines or FDA labeling that cites a 10% cross-reactivity rate. But research since the 1990s has shown this number is inaccurate. A 2021 survey found that 80-90% of providers still believe the old 10% myth, even though major medical societies have updated their recommendations. Education and access to allergy testing are key to changing this.

Are there any cephalosporins that are completely safe for everyone with penicillin allergy?

No antibiotic is 100% safe for everyone. But third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins - like ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, and cefepime - have side chains so different from penicillin that cross-reactivity is extremely rare. For patients without a history of IgE-mediated reactions, these are considered safe alternatives. First-generation cephalosporins like cephalexin carry higher risk and should be avoided in those with confirmed IgE-mediated penicillin allergy.

Jeffrey Frye

December 25, 2025 AT 09:35so like... i got slapped with a penicillin allergy label in 2008 after a rash from amoxicillin. never had hives, never choked, just kinda itchy. now i’m 35 and every time i need an antibiotic, docs act like i’m holding a live grenade. turns out i probably just had a side effect? wild. glad this post exists.

Dan Gaytan

December 25, 2025 AT 12:39YES. 🙌 I’m a nurse and we’ve had 3 patients in the last month who got stuck with vancomycin because of ‘penicillin allergy’ - turns out they were kids when they got the label. One had a stomach ache. 😅 We’re pushing for allergy clinics here. So much waste. So much risk. Time to update the system.

Usha Sundar

December 25, 2025 AT 19:05My aunt got ceftriaxone last year. No reaction. She’s fine now. Doctors still scared.

claire davies

December 26, 2025 AT 20:24Oh my god, this is one of those posts that makes me want to hug every doctor who’s brave enough to question outdated protocols. 🤗 I’m from the UK and we’ve had this same mess for decades - penicillin allergies on every chart like some kind of medical tattoo. But here’s the kicker: I had a cousin who got anaphylaxis from penicillin at 7. She’s 42 now. Got tested last year. Negative. Now she takes amoxicillin for UTIs like it’s candy. And she’s alive. And well. And that’s the point - we’re not being careful, we’re being *lazy*. The side-chain thing? Mind blown. Like, imagine if your phone case was the only thing triggering your allergic reaction to your phone - not the battery, not the screen, just the damn case. That’s what’s happening here. We’ve been blaming the whole device for a sticker.

Chris Buchanan

December 28, 2025 AT 17:36So let me get this straight - we’ve been denying 30 million people better antibiotics because of a 1970s lab error... and the FDA is still on the ‘10%’ bandwagon? 🤦♂️ Meanwhile, people are getting C. diff from vancomycin because we’re too scared to use a $5 drug that works. This isn’t medicine. This is medical superstition with a prescription pad.

Wilton Holliday

December 29, 2025 AT 21:06As a med student, I’m so glad I learned this in my immunology class. We were taught the 10% rule in year one - and then in year three, our allergist guest lecturer laughed and said, ‘That’s why you’re killing patients with clindamycin.’ I’ve already told my grandma to get tested - she’s been avoiding all antibiotics since 1982 after a rash. She’s gonna be shocked when she finds out she’s probably fine. Keep spreading this info - it’s life-saving.

Raja P

December 30, 2025 AT 01:24in india too, doctors still avoid ceftriaxone for penicillin allergy. even when it's the only good option for pneumonia. patients are scared too. but i told my uncle to ask for testing. he’s 68, had a rash at 12. now he’s on ceftriaxone for bronchitis. no issues. maybe we just need to talk more.

Joseph Manuel

December 31, 2025 AT 19:07The assertion that cross-reactivity is below 1% for third-generation cephalosporins is statistically misleading. While aggregate data may show low rates, individual risk stratification remains critical. The absence of IgE-mediated reactions in retrospective cohorts does not equate to absence of risk in prospective clinical practice. Furthermore, the FDA’s labeling reflects precautionary principles grounded in pharmacovigilance, not outdated science. Dismissing regulatory warnings without robust, prospective, multi-center validation is clinically irresponsible. The burden of proof lies with those advocating deviation from established labeling - not the other way around.

Delilah Rose

January 1, 2026 AT 17:20I work in a rural ER and I’ve seen this firsthand. A guy came in with strep throat, said he was allergic to penicillin - so we gave him azithromycin. He came back two weeks later with a peritonsillar abscess. We had to drain it. He was in pain for weeks. If we’d just given him ceftriaxone, he’d have been home in two days. I’ve started asking patients: ‘What happened when you took penicillin?’ If they say ‘I got a rash,’ I say, ‘Okay, let’s talk about whether that’s really an allergy.’ Most of them don’t even know the difference. And honestly? Most doctors don’t either. It’s not that they’re bad people - they’re just trained on old info. We need more continuing ed. We need posters in waiting rooms. We need pharmacists to push back. This isn’t just about antibiotics - it’s about how we think. We’re still treating medicine like a rulebook instead of a living science.

Aurora Daisy

January 3, 2026 AT 01:25Of course the FDA hasn’t updated the label. Because if they did, you’d have Americans suddenly taking antibiotics like they’re candy. We’ve got a whole nation of hypochondriacs who think a sneeze is a pandemic. Let them keep their vancomycin. At least it’s expensive and makes them suffer a little. Maybe then they’ll stop asking for antibiotics like they’re Starbucks lattes.